By Ben Brown

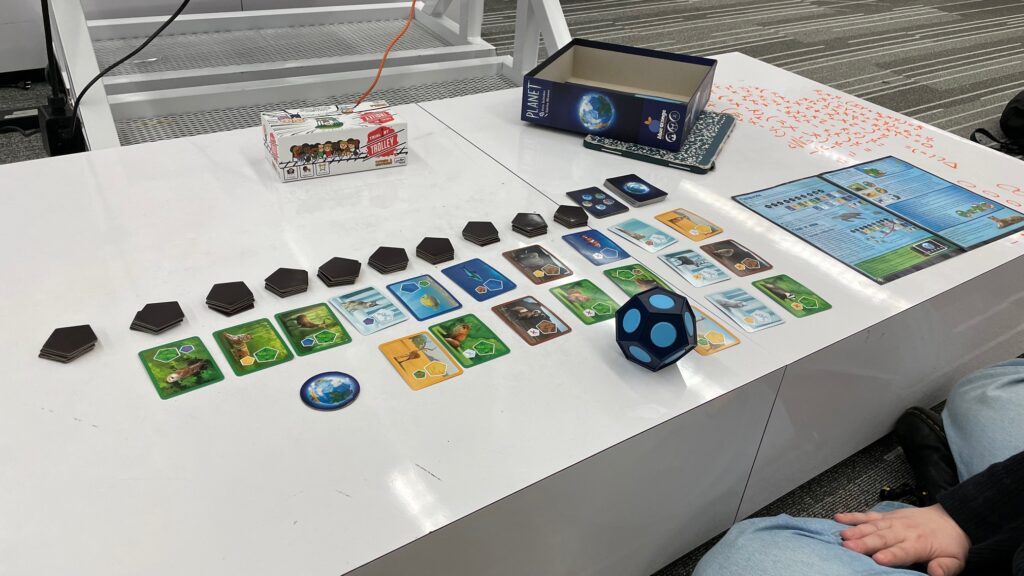

Planet by Blue Orange Games is a game for 2-4 players about building a planet by placing pentagonal tiles on a dodecahedron. Each tile has different colored areas that represent different habitats, like forest, ocean, and desert. Each round, players pick a new tile and put it on their planet, and then earn “animal cards” based on how their planets are constructed. At the end of 12 rounds, the player with the most animal cards is the winner. A game takes ~30 minutes.

The Materials

The thing in this box that grabbed the attention of everyone I have played this game with, board game newbie and veteran alike, are the four dodecahedra. There is something inherently fun, satisfying, and tactile about placing these tiles, which are held on by magnets, on your planet: it makes Planet stand out the moment you open the box. Players have to build around a geometry they’re not used to, one where they can’t see all the sides at once and have to rotate around and keep track of things in their head. This can make it tricky to judge the sizes of your planet’s habitats (something you do to earn animal cards) but I didn’t find it too big of an issue. While the magnetic tiles are easy to remove, they are also easy to spin accidentally, something that is a big problem since the rules forbid you from moving a tile once it’s placed on your planet. Speaking of the rules…

The Rules and Setup

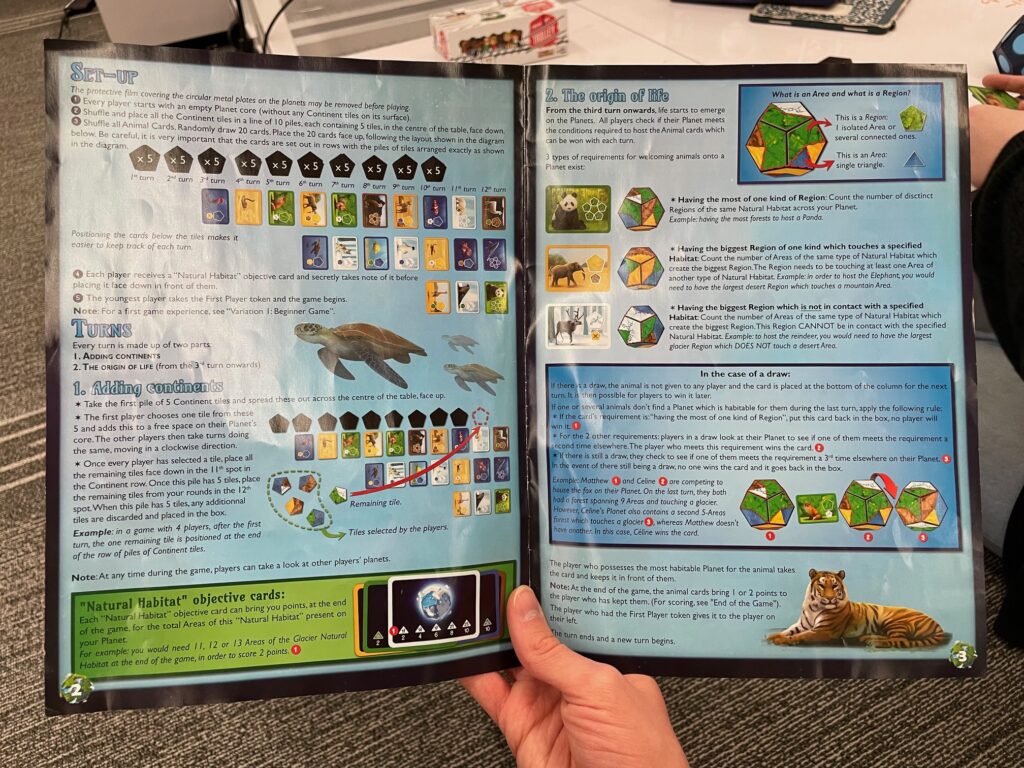

The rules for this game are fairly explicit, and while not too long, do take a little time to fully grasp. You have to learn some terminology like the specific difference between an “area,” “region,” and “habitat,” but I didn’t mind them. However, I have a couple nitpicks. The first is that it doesn’t seem to state that the person who gets first pick of tile should change each round, despite the fact that having first pick of tiles is a huge and obvious advantage. We fixed this easily by just passing the First Player token to the right each round. The second (which is mainly due to me being a math major) is that it could have been clearer that two areas are only considered “connected” if they share an edge, not just a vertex.

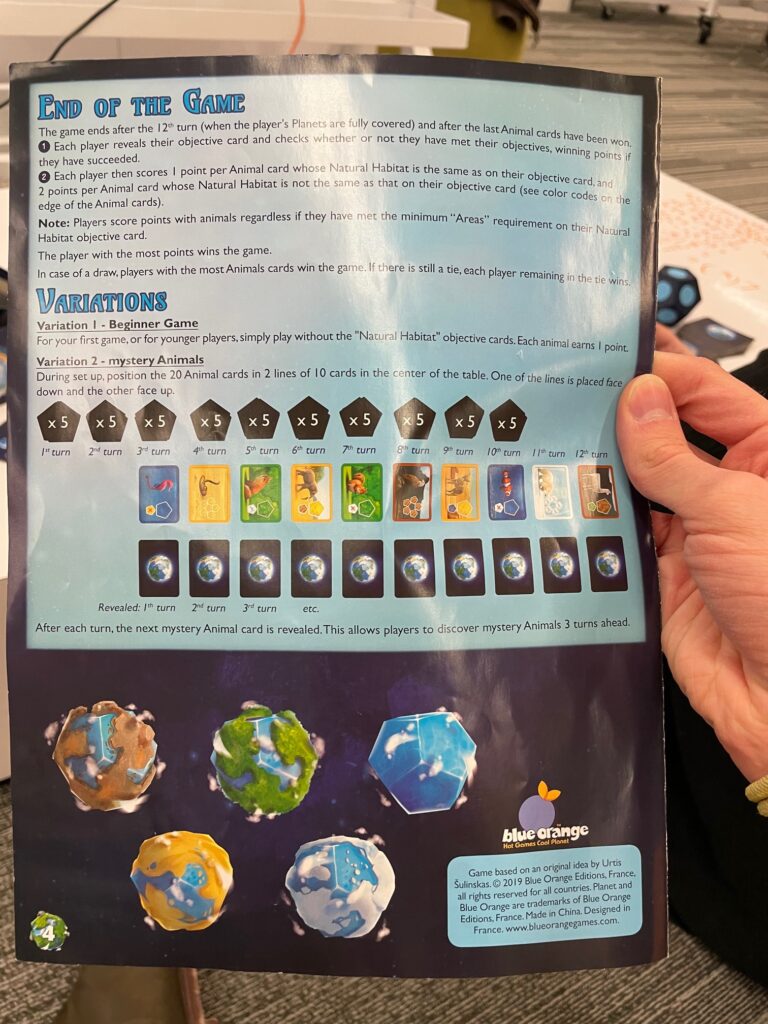

The setup of this game is my least favorite part. If you look at section of the rule book entitled “Set-Up” you see a picture of a bunch of cards and tiles and are told “Be careful, it is very important that the cards are set out in rows with the piles of tiles arranged exactly as shown in the diagram.” If cards and tiles are not kept in neat little rows and columns, like in the picture, you can easily lose track of which round it is. The single biggest improvement Planet could make would be to include a board with outlines for where all the cards and tiles go, so it’s easy to tell when something’s out of place.

The Gameplay and Objectives

Each round, five tiles are drawn and players go in a circle taking one and adding it to their planet. Then animal cards are awarded to the player whose planet meets the condition on the card. While the animal cards for each round are on display to everyone for the whole game, the batch of tiles that players choose from each round are a surprise, enabling players to plan ahead about what kinds of tiles they should choose, while keeping an uncertainty about whether their plans will work. For instance: say I see a lot of animal cards in the next three turns require having a lot of Glacier areas. I plan on choosing a tile with a lot of Glacier areas on it, but when the tiles are shown for the next round only one has any Glacier on it. Another player then takes that tile before it’s my turn, so I have to either do the next best thing or come up with a new strategy.

The animal cards, I think, are very intelligently designed because of how they offer conflicting incentives to how you choose and place tiles on your twelve-sided world. Each animal card is specific to one habitat (forest, ocean, etc.) and have one of three conditions:

- Having the most regions of that habitat, regardless of their individual sizes.

- Having the biggest region of that habitat which touches a specified different kind of habitat

- Having the biggest region of that habitat which does not touch a specified different kind of habitat

These conditions are at odds with one another: 1 incentivizes you to spread out your areas of the same kind to make many small, unconnected regions, while 2 and 3 incentivize you to consolidate them all into one big region. 2 rewards you for building a region that touches as many other kinds of habitat as possible, while 3 rewards you for building one that touches as few as possible. This means that getting a lot of cards, even if they’re all for the same habitat, is a balancing act that benefits from some careful planning and requires sacrifice. After playing the game only a couple times, I could tell this system was very well thought out.

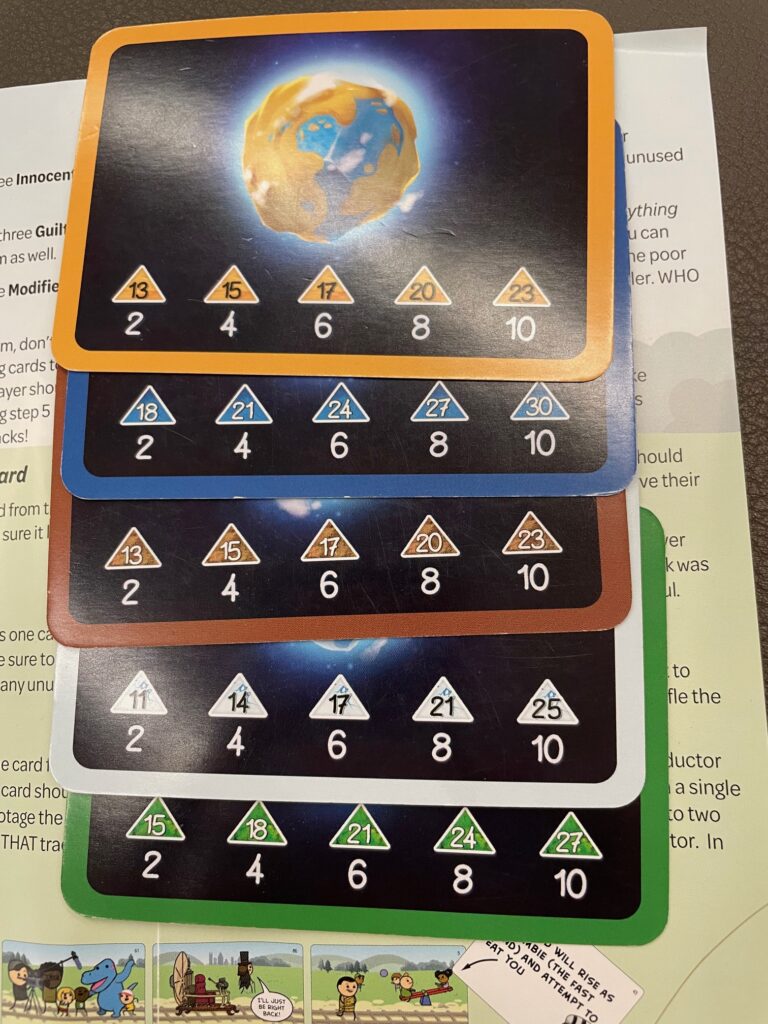

These cards also play into the strategic trade-off of “do I want to make my world a more even variety of habitats, or do I want to min-max my world and cover it with one or two habitats.” The former strategy means you’ll be in the running for more animal cards, while the latter makes you more competitive for a few cards and less for all the others. Adding to (or perhaps detracting from) this decision are the optional “Natural Habitat” objective cards. Each player gets one at the start and it awards them points at the end for how much of a specific habitat they have on their world.

These cards can offer big bonuses for players who really try hard to cover their world in a specific habitat, and I think incentivize the min-max strategy a lot. However, I don’t think they make that approach the be-all-end-all you must use if you want to win. Overall, while I believe these cards do make the game more interesting and fun, playing without them isn’t a huge loss (at least for newer players).

Conclusion

While I played Planet, I was somewhat reminded of my favorite board game of all time: Ticket to Ride. Both games center around strategy planning that relies on drawing and picking cards to build something which can satisfy multiple kinds of objectives, as well as be messed up by other players’ actions. Both are also much more fun with more players. In terms of gameplay, I enjoy Planet less: while Ticket to Ride takes longer to learn the rules, long-term strategies in that game come more naturally. Planet’s dodecahedra make it harder to discern your opponents’ goals and sabotage them since all the pieces aren’t together on one board (sabotage is, in my opinion, the best aspect of Ticket to Ride.) While Planet did not become my new favorite strategy game, it is certainly a fun and competent one, and turns an oft-overlooked part of gameplay (placing tiles on a board) into its most unique feature and arguably its greatest strength.