by Ben Brown

Something people may not know about me is that I greatly enjoy improv. I have taken a lot of improv classes in the past and I have even taught it a couple times. I know how hard improv can be, and I know that creating long-form improv that tells a story over the course of multiple scenes is especially difficult. This is why Fiasco, a game about improvising a story over multiple scenes with no Game Master to oversee everything, caught my interest. Could people learn how to do longer-form improv scenes from playing this game? How does it compare to other improv games?

In a standard improv game, you typically get a prompt from the audience that describes either a setting, object, or relationship, as well as an additional rule that sets the game apart (e.g. one person must be sitting in a chair and one must be standing the whole time). The rest is left up to the people in the scene, but there is a rule of thumb that in the first three lines of dialogue, you should establish the following:

- Who you are in relation to one another (in my opinion, the most important of the three)

- Where you are

- What you’re doing

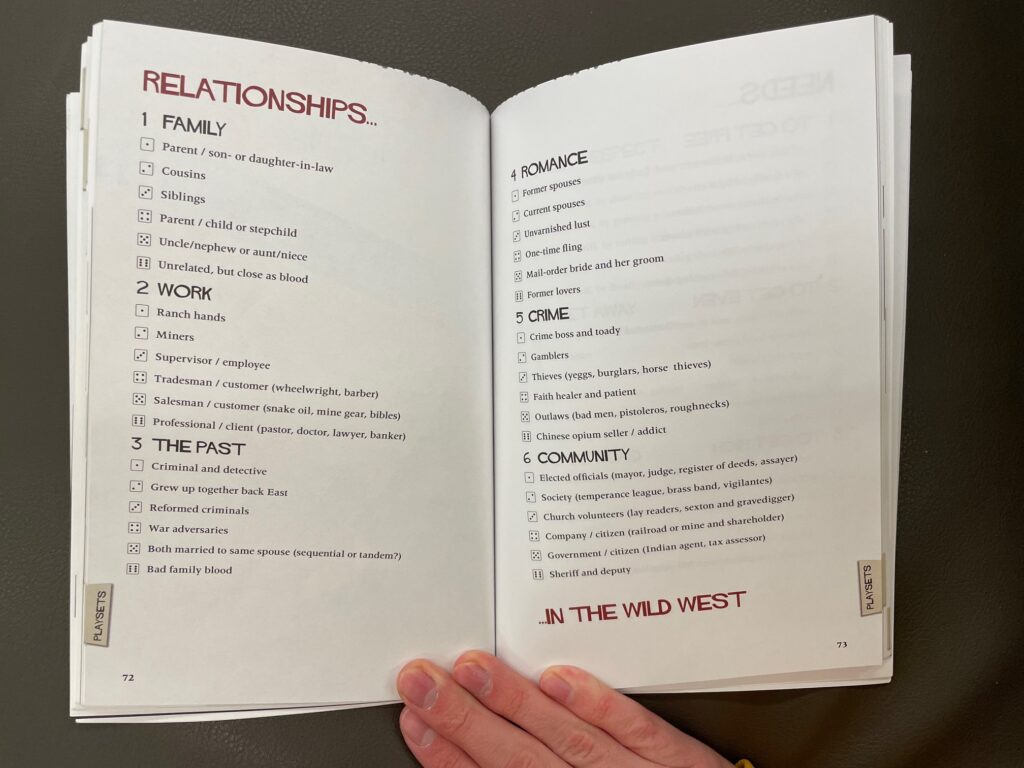

Fiasco begins with a setup phase that shows it understands these rules very well. Via a combination of player choice and randomness, players get relationships and details about those relationships from a table in the book. Fiasco makes sure every pair of players have a relationship (e.g. “mail-order bride and groom” or “church volunteers”). In addition, some pairs of players get shared “needs,” which are shared goals that can be vague (“get rich through violence”) or more specific (“get rich by robbing a bank”), and shared objects. There is also a location chosen from a table.

NOTE: I played the Classic version of Fiasco, where these things are drawn from a table via rolling dice. The book contains multiple tables (called “playsets”) which provide a good variety of types of stories. My main issue with this version of Fiasco is that it requires you to have four six-sided dice numbered 1 to 6 for each player, half of which must be one color and half another color. There is a newer version of Fiasco which solves this issue by using included cards instead of dice, but it costs $5 more and doesn’t lend itself well to creating your own playsets, which is much easier with the Classic book.

In terms of creating details that tie all the scenes together, Fiasco’s system does (nearly) all the work for players. They don’t have to imagine or agree on a lot of essential details, they just make a series of individual choices. This hand-holding is good for people who are new to improv, as you can get into making good scenes, but you may not learn to do it on your own this way. Speaking of which…

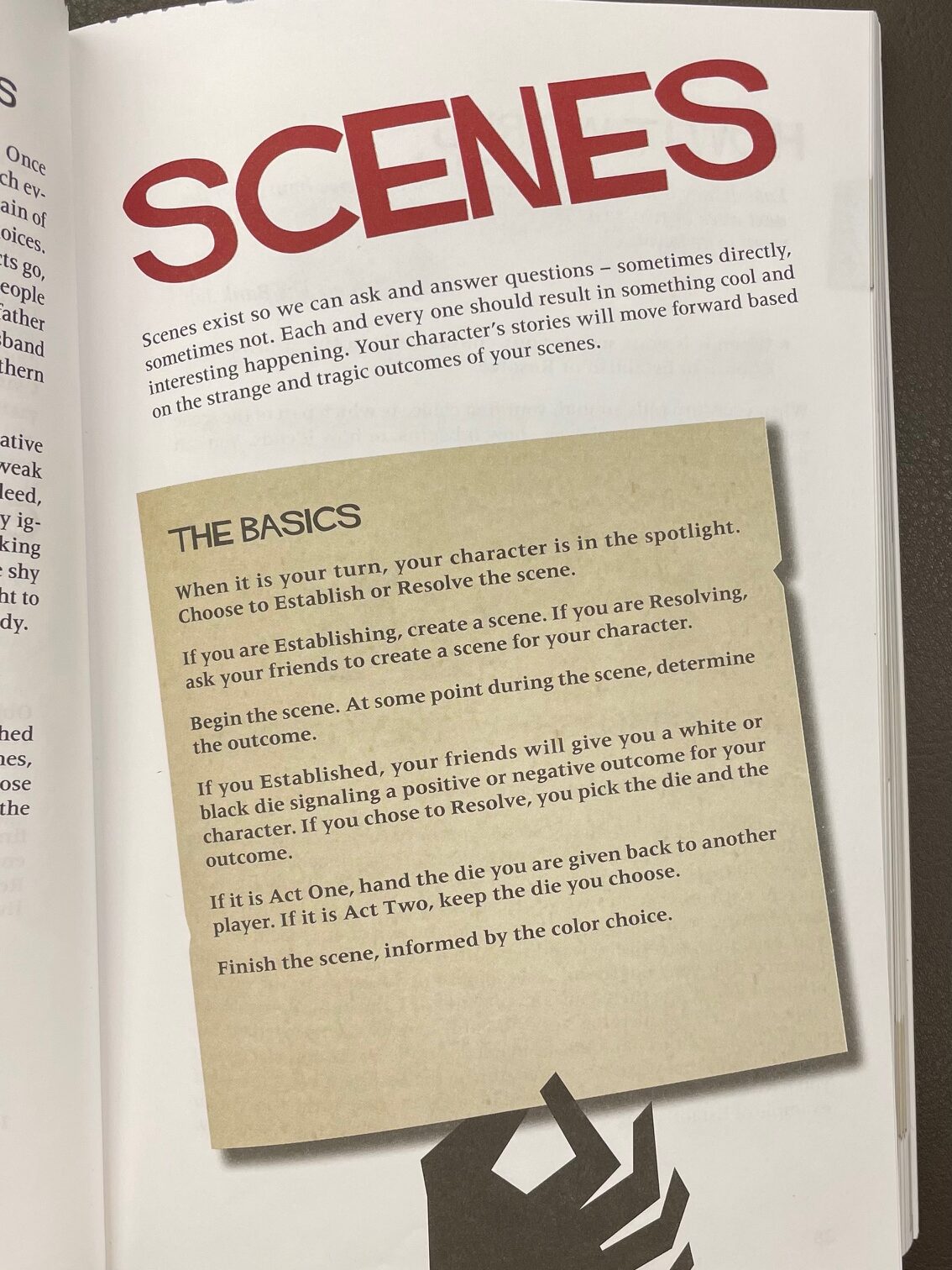

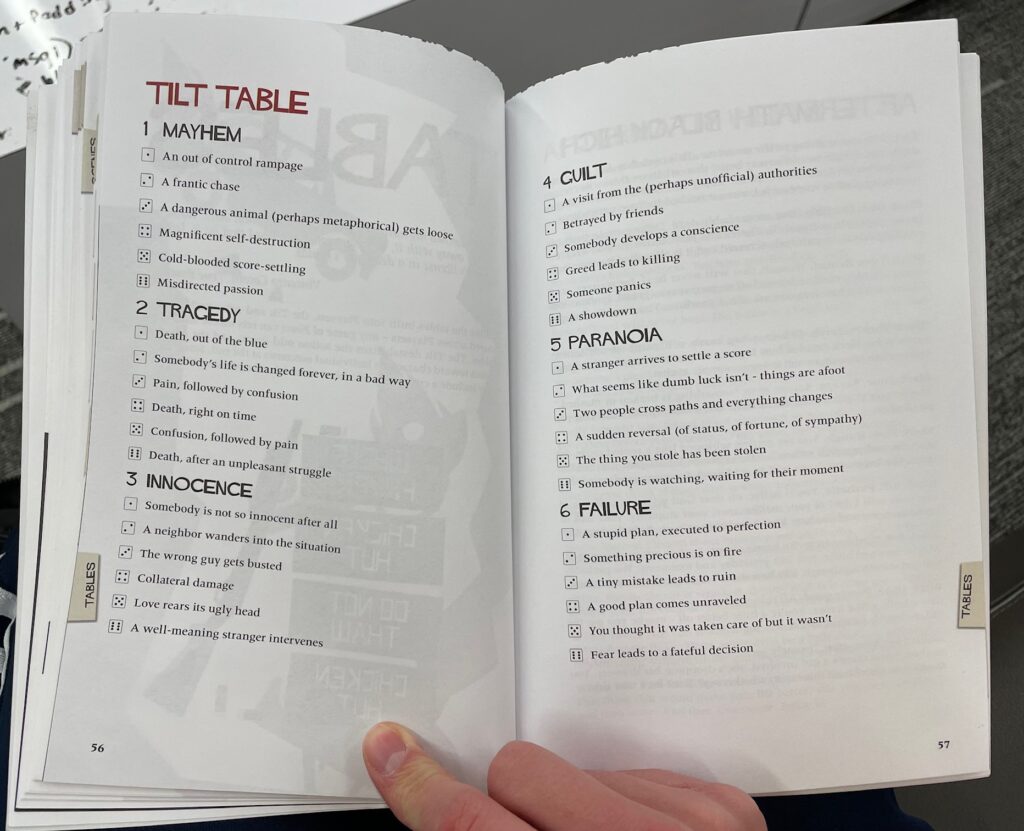

The actual scenes players do in Fiasco are split into two acts with each player leading two scenes in each act. In a scene, there are two duties: Establish and Resolve. The player leading the scene chooses to do one, and the other players do the other. Establishing means setting the context for the scene: describing what the characters are doing, where they are, etc. Standard stuff that people in improv scenes do, albeit with more structure and guidance to help people who are new to improv. Resolving is more unique: it means deciding only whether the scene’s outcome is good or bad for the character of the player whose turn it is. This extremely vague approach is actually really great: it gives players enough to have something to work towards but still have a ton of freedom to decide what that is and how they get there when they actually do the scene. An event called the Tilt also happens between acts where players choose a twist in the story from another table. This keeps scenes fresh as the game goes on.

Establishing and Resolving give players enough guidance to produce good scenes that tell a story without the game doing any of the actual work for them like in the setup. Many improv scenes end up as two people making jokes until someone tells them to stop, but with these simple instructions players have to think about how their scene begins and ends. For this reason I think playing Fiasco prepares players well to do individual scene improv, albeit with one or two missing instructions. The “scenes” section of the book contains some helpful tips on how to make good scenes, and you can buy a companion book that allegedly has a lot more (but that’s for another review.)

However, I noticed something strange about Fiasco’s instructions: they don’t really tell players they need to act out scenes. The example game in the book has people acting them out, but your group can also take a more descriptive approach: telling the story together versus acting in it. This is what my group did when we played Fiasco, and it seems that players gravitate to whatever style the group enjoys the most, which is cool! (I may steal this idea for my project.) The exception to this rule is the Aftermath at the end of the game, where players are explicitly told to describe what happens to their character at the end rather than acting it out, so the ending doesn’t drag on too long. I think this decision is fair.

I believe that Fiasco is a really good introduction to shorter-form improv, if you choose to play it that way, due to how it directs players to begin and end scenes and the tips it provides. To learn how to do longer-form, multiple scene improv on your own from this game, you really have to analyze its rules and ask why it does what it does. While playing Fiasco isn’t a perfect substitute for actual improv exercises and classes, it succeeds in getting players through the hard parts of improv so they can enjoy the meat of acting out scenes, and might just inspire you to pursue improv further.