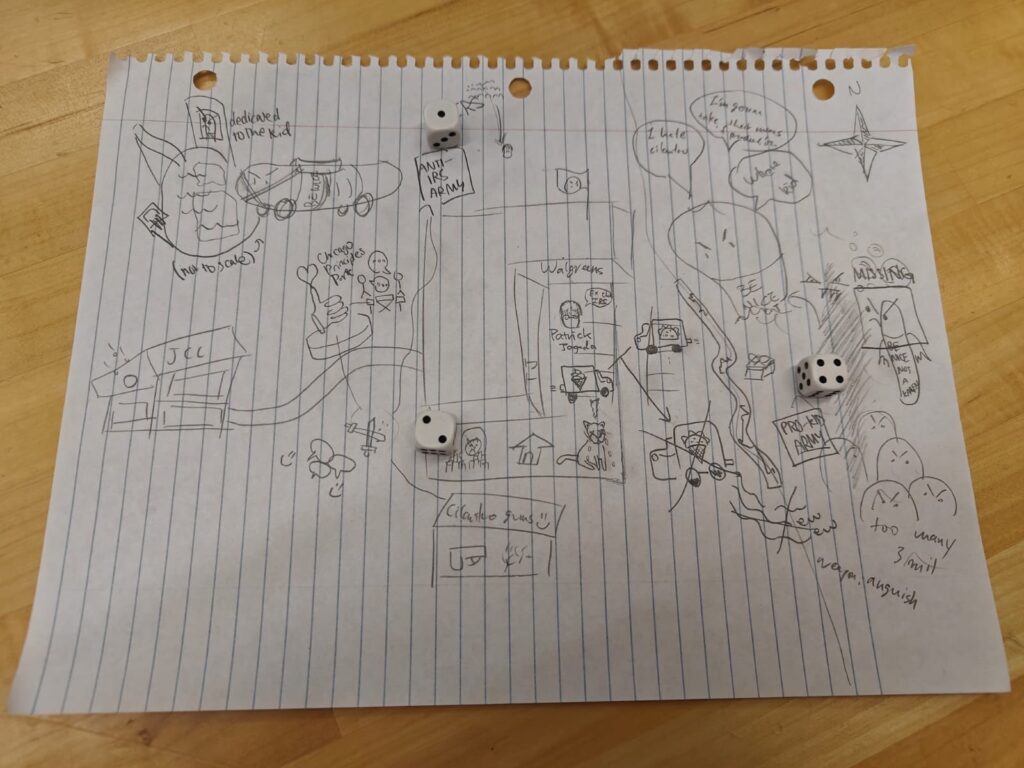

When Yiming, Sanaiya and I opened the burlap sack that contained The Quiet Year (which in and of itself is a genius piece of thematic design, by the way), I certainly did not expect our year of survival as a post-apocalyptic community foreshadowed by the potential arrival of the Frost Shepherds would end up taking place in the parking lot in front of our local Hyde Park Trader Joe’s, not to mention the hordes of sea monsters that hate cilantros and the inexplicable presence of the IRS, apparently the last remnant of government in this barren world.

Gameplay and Narrative

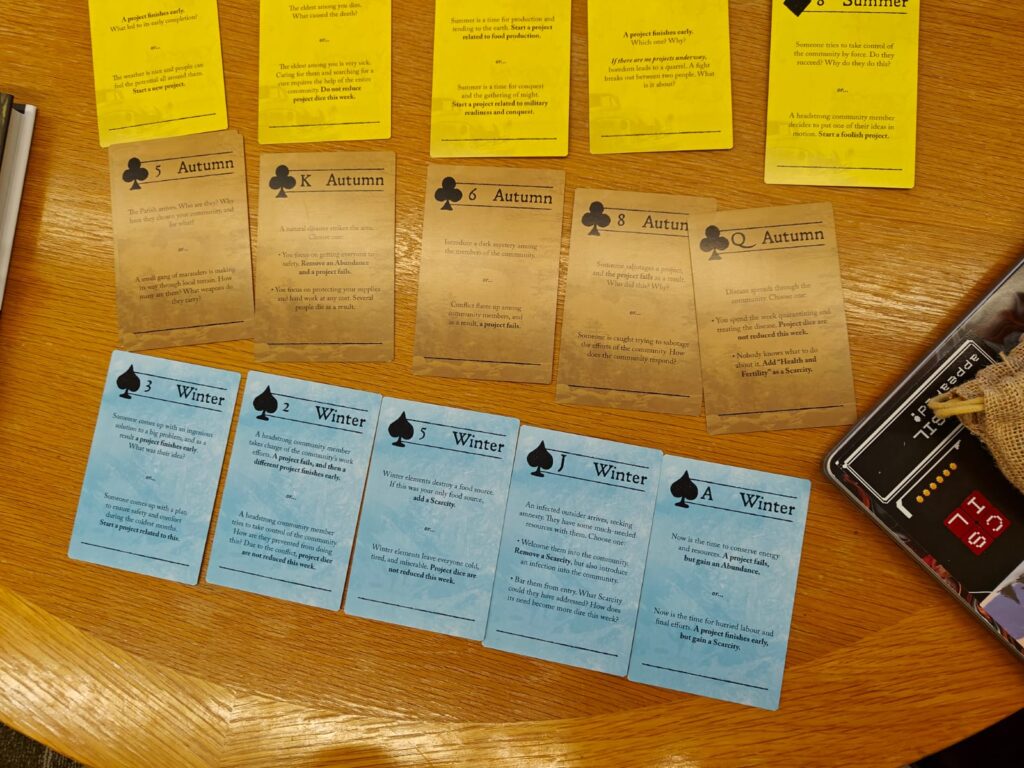

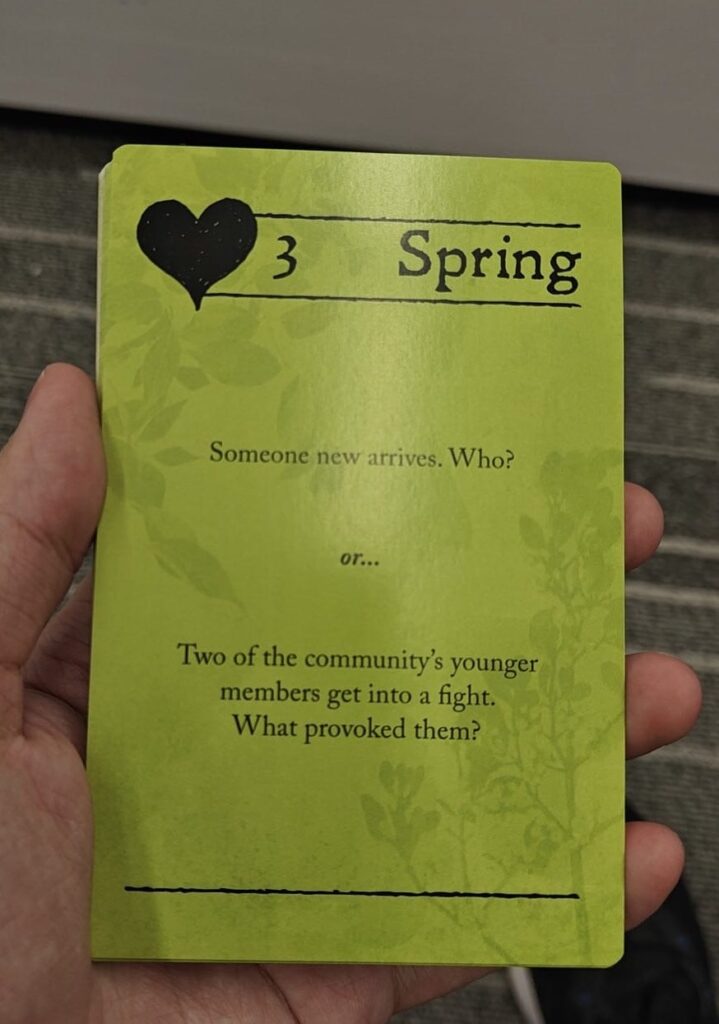

The core gameplay of The Quiet Year revolves around a deck of cards and a map. The players collectively represent the social forces within a community that seeks to survive in a post-apocalyptic setting, and the general direction of the narrative is controlled by the deck of cards separated into four seasons.

This guided emergent narrative structure divided into four seasons is central to the progression of The Quiet Year’s experience. While players have significant freedom in interpreting the instructions given on the cards, these open-ended prompts differ across seasons and, like an invisible hand, pushes the narrative towards a general direction of less and less wholesome.

While spring is more about building the stories and basic information of the community, negative events would gradually become more and more frequent throughout the year, with cards that have one good option and one bad becoming rarer and rarer. Eventually, bleakness in full swing during the winter rounds up the narrative with the sudden arrival of the Frost Shepherds – the ending of the game, represented by the draw of a random card (which we got literally on the first day of winter in our playthrough).

Nonetheless, this guided emergent narrative still offers plenty of player freedom – the game of Hyde Park Trader Joe’s that we played would serve as the best example – it showcases the adaptability of the game’s mechanics to various themes and settings, and players are able to let their imaginations roam with considerable freedom, while also reaching a delicate balance between “too much rules” and “too much freedom.”

Roleplaying as Social Forces, and the General Will

Notably, despite labeling itself as a map-drawing game, the mechanics in The Quiet Year that impressed me the most are actually discussions, projects, and contempt, through which the game intricately ties into sociological theory regarding the conflict between the individual and the social.

In The Quiet Year, players are not roleplaying as any particular individual, but as abstract social forces. As the game progresses, the guided narrative provided by cards introduce a myriad of different conflicts within the community, and players – representing abstract social forces – inevitably end up taking sides and representing interest groups within the same community. When the sea monster appeared in our game and threatened the existence of our community, for example, two separate factions emerged, one standing by the pacifist ideals exemplified by the community’s Chicago Principles Park, and the other taking a much more militaristic stance in their factory of cilantro guns.

French philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his work on defining the social contract, outlines two sociological concepts: the general will and the particular will. The general will refers to the collective will of the citizens of a society, the common good or common interest. It is not merely the sum of individual desires (which might, and often do, conflict with each other), but rather focuses on what is best for the society as a whole. On the other hand, the particular will(s) are individual desires or interests of a person or a group. These are specific wants that may or may not align with the common good.

The Quiet Year encourages players to represent the general society and think about the common good of the community they are building, thereby attempting to represent “the general will”. As players draw cards and face various scenarios, they have the community’s development and survival as the “general will” in mind. However, each player may have their own visions for the community’s development, represented by specific projects, resources, or responses to events that they prioritize. Players are constantly presented with these conflicts of interest, and navigating these reflects Rousseau’s idea that a well-ordered society (or in this case, community) must find ways to align the particular wills of its members with the general will to ensure collective well-being.

In short, The Quiet Year offers an interesting reflection on the dynamics of social contract and governance in real-world communities. It illustrates the complexity of balancing the interests of particular groups with the idea of a “common good,” and challenges players with decision-making that benefit the community as a whole in spire of the constant presence of discord, tying into a larger philosophical discussions on democracy. Of all the good that comes out of The Quiet Year, I think that this is its crowning achievement: a philosophical representation of the fragile yet crucial balance between social discord and concord, translated into playful experiences through well-crafted mechanics and rules that supported an emergent narrative based on abstract social forces.