I: Introduction

(Written by Laura)

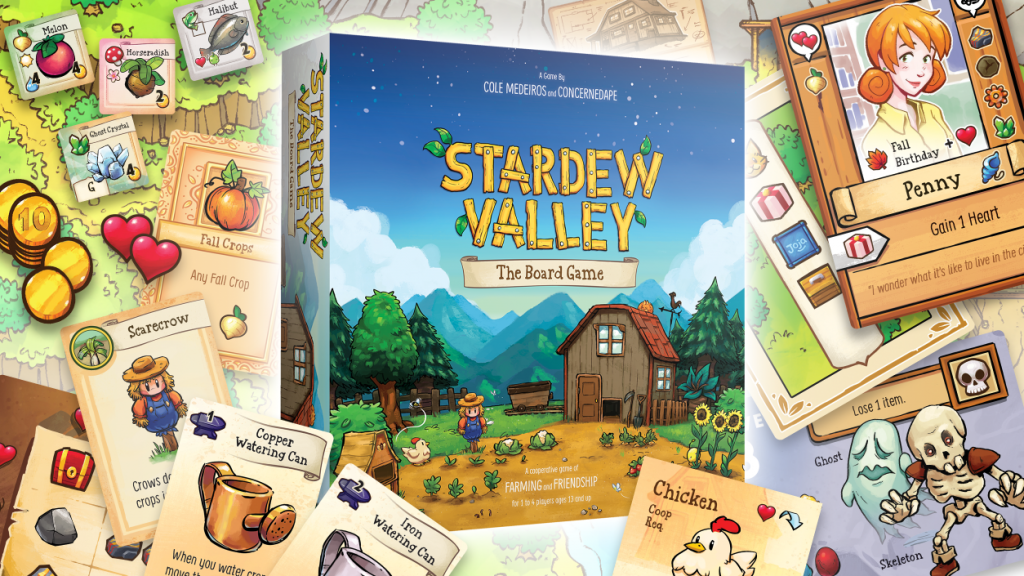

Although the tabletop version of Stardew Valley is a cozy game with a variety of intricate mechanics, one can also create artificial conflict and story. This happened many times throughout our playtest. What sets Stardew Valley apart from other cozy games is that it has a variety of mechanics including farming, fishing, crafting, mining, and even making friends along the way! There is also a sense of surprise when players reveal hidden objects, random events, roll some dice, and even draw from a mystery bag. In addition there is a company that tries to make the experience all more difficult: Joja. If you want this company’s restraints to go away, players must pay a heavy price. This game is cozy with resource gathering, strategy, and even relationship making. This game has it all. In our game, there was even some artificial conflict when it came to relationships…read some more!

II: Mechanics & choices

(Written by Yiming)

The video game Stardew Valley includes many mechanics, such as farming, fishing, mining, etc. As a board game version of the video game (like the Portal’s board game: The Uncooperative Cake Acquisition Game) the analog Stardew Valley here does a great job reproducing the video game experience as closely as possible.

The objective of the game is to fulfill four goals given by the player character’s grandpa within a year, as well as complete six “resource bundles” in the local community center. The goals are tied to the mechanics of the game, such as making a number of friends or having a number of animals. Players first choose their professions (farmers, miners, etc.) in the game and select their starting tool, which grants them certain special skills that help them during the game. Before the game begins, one player is assigned the pet token, which indicates who will take the next turn. Then in each turn, the pet token holder draws a season card, which represents a day in the game. The season card appoints several actions that the player needs or may complete, such as passing the pet token to the next player, obtaining a gift from a friend, or watering the crops. After performing the actions on the season card, the player has two options:

- Start at any location on the map and complete two actions appointed by that location, or

- Start at any location on the map, perform one action appointed by that location, move to one adjacent location, and perform another action of the new location. Here, they may use money to buy crop seeds and plant them, fish at the lake/ocean/river, explore the mine, make a friend, etc. Ultimately, the game encourages all the players to work together and plan out their actions to fulfill Grandpa’s goals.

The mechanics of the board game successfully reproduce the freedom of choice in the original video game through the action phase. Here, the players are allowed to choose any location to start their turn, unlike most board games where players start in a predetermined location and progress onward. This also helps the players plan their actions according to the goals they want to fulfill. In our play session, the players soon realize that they should have precise roles to maximize their turn and progress towards the goal as quickly as possible. Combined with a plethora of actions that the players can choose from, the game also provides a storytelling opportunity: in the cozy town, players gather together for the same objectives. Some of them might make more friends, and some of them might spend more time farming/fishing.

All choices and actions have clear meanings and feedback, which helps the player to further plan out their action as they learn to play the game and work in a team. Every turn, the player is specifically given the opportunity to make two actions beyond what’s on the season cards. Their choices are immediately reflected in the game through the mechanical actions that they need to do, such as rolling dice for fishing or buying animals, spending money to buy crop seeds. The outcomes of those actions are feedback of the player’s choices. Take fishing, for example: the player may or may not get the fish they want, depending on the dice rolling results. The meaning of those actions typically relate to the overall objective of the game, assuming that every player works towards the goals assigned to the game. A player may choose to spend their two actions in their turn on fishing to make enough money to buy animals, if the goal requires all players to have a certain number of animals combined. However, the mechanics also allow players to imbue personal meanings that don’t relate to the game at all. Instead of working towards the assigned goals, a player might choose to make as many friends as they can, and friend making is not an assigned goal since inherently, the actions don’t have predetermined meanings.

The board game also successfully reproduces the coziness of the video game. Unlike the video game where time passes no matter what you do, the board game does not have a timer, and the players can take as long as they want in considering their actions during their turn.

III: Let’s make some “friends” (& maybe an enemy)

(Written by Sanaiya)

Remember Grandpa? He doesn’t like the idea of his spawn being lonely & friendless. One of the many goals he could assign to Stardew Valley players involves collecting a certain amount of love from the villagers before the endgame. As you may expect, this fun, friendshippy goal links up nicely with the game’s relationship-building mechanic.

Straightforward, right?

No.

Interpersonal interactions are messy, even within the confines of a cozy game. And Stardew Valley’s relationship-building mechanics, at least during our team’s gameplay, threatened to tear asunder the collaborative fabric of Stardew’s coziness. Many an agricultural…uh…tool-themed insult (that I don’t care to repeat here…use your imagination) was hurled as we fought over the companionship of a fictional villager** named Jodi.

“Jodi was not supposed to be a point of conflict. But we were fighting over her in a kinda cozy way.”

Andrew

So, let’s zoom in, talk about what makes the relationship-building mechanic a uniquely engaging, welcomely out-of-character aspect of Stardew Valley.

- How does the mechanic work? Bribery is Stardew Valley’s (rather accurate, if cynically transactional) approximation of how a relationship works. One of the actions a player can take after completing all the tasks on their season card is “Make a Friend.” Take a card from the villager deck, and if the resources in your inventory line up with the villager’s taste in gifts, they’ll shower you with hearts, the in-game currency of charisma. (Hearts theoretically belong to all the players, although the way we played the game did not exactly…uh…support that idea. Please see section VI for further discussion!) In actuality, hearts are good for warding off Joja, better for cultivating a thriving community center, and best for blurring the boundaries of the game’s magic circle: where does the in-game drama end—and the real-life drama begin?

** What do you mean Jodi’s a fictional villager? You and Laura fought over her as if she was alive.

Yiming

- How did we corrupt the mechanic? Jodi, a devout vegan, graciously accepted my plant-based present in exchange for her friendship—or, as Laura would interpret it, her undying love. Cue some unexpected choice feedback: her Jodi-shaped jealousy. The ambiguity of what it means to have a “relationship” with the adult-age villagers lends itself (too) perfectly to in-group fighting. As such, we lost sight of Stardew Valley’s larger objective, narrowing in on the petty, parasocial Jodi drama. (She’s canonically married; what are we even doing?). This is an artificial conflict layered atop a whole host of artificial conflicts, a jewel atop the crown of this game’s cognitive/emotional engagement (nothing in the game caused as much laughter as my and Laura’s semi-serious, semi-theatrical back-and-forth over whom Jodi’s hearts belonged to). Regardless of the answer (spoiler: it’s Laura), Jodi allowed us to make our playthrough of Stardew Valley our own—and for the memories…the hostile, hilarious memories…I will be forever grateful to her.

“I loved how much we got to express ourselves through this game.”

Rachel

IV: Challenges (i.e. how time is slowly slipping away)

(Written by Rachel)

To see what the challenges of Stardew Valley are, we can work backwards from our goals. Let’s recap: in Stardew Valley, the player’s goals are to complete four of Grandpa’s goals and complete the six community center bundles before the year ends. Grandpa’s goals can include activities like raising animals, making friends, and exploring the mine. These activities all take time, resources, or both. For instance, making friends requires the time spent to go to the village and meet new villagers, but it also requires giving them gifts that they like, consuming resources. Community center bundles are completed by collecting specific resources. Now, how do we collect said resources? Well, that simply takes time! Time to grow crops, time to catch fish, time to explore the mine, and more! A critical thing to note is that collecting resources does not ask anything of the players other than their time.

Ultimately, the challenge in Stardew Valley revolves around how players choose to spend their time. Sure, the game does have an antagonist, Joja, that actively puts barriers in the way of your progress through the game. However, all of these barriers may be bypassed through spending resources, which are acquired through spending time! Moreover, Joja’s interventions are tied to the progression of the seasons, meaning that players are rewarded for taking actions faster—before Joja’s barriers appear. The true driver of conflict in the game is the passage of time, as the final measure of the players’ success is whether or not the players were able to achieve their goals before they ran out of time.Players have a wide variety of equally valid strategies for overcoming the challenge of their limited time, allowing for players to express themselves via their preferred tasks. For instance, in our game, one of Grandpa’s goals was for us to raise a certain number of animals. To do this, we needed to build a farm building, and to build one of those, we needed to obtain money, and in order to obtain money, we needed to sell resources. Each player chose their preferred way of obtaining resources to sell: some of us grew and sold crops, and some of us went fishing to try to try our luck at obtaining a (valuable) legendary fish. Once we obtained the money, we needed to choose what kind of building we wanted to build and what kind of animals we wanted to raise. This example is illustrative of the appeal of Stardew Valley: it was not very strategically important how exactly we went about obtaining the money and what pets we chose to buy, meaning that our choices were able to reflect the activities that we personally enjoyed doing.

V: Conclusion

(Written by Andrew)

Playing Stardew Valley the board game was an essential experience for our group’s understanding of the idea of coziness, both as subjective player experience and a more general genre for games. Fundamentally, the board game version of Stardew Valley seeks to carry over as many mechanics from the video game as possible, translating and preserving them in the tabletop format. In doing so, the board game successfully preserves the original feeling of player agency and freedom of choice in pursuing goals that formed a crucial aspect of the potential coziness of Stardew Valley the video game. (“Potential” because you can totally be a tryhard in the original video game, min-max everything, and cover the entire Valley with wine casks and kegs. But hey, where’s the FUN in that? You’re just becoming the embodiment of capitalistic pursuit of surplus value and estrangement of labor from which you sought to escape!)

Additionally, as discussed in detail above, Stardew Valley the board game also succeeds, despite its coziness, in both allowing players to create artificial conflicts and presenting them with challenges that revolve around time management—another aspect dutifully preserved from its video game predecessor (albeit in a much less stressful way, as there are no real-world time limits to the length of each day, but rather a turn-based time system) that adds a layer of strategic depth to the players’ resource management. Still, a wide array of available strategies are perfectly balanced with regards to player freedom and preference to ensure a cozy experience.

VI. The Big Misconception—and how it changed everything

Well, it seems like unfortunate news have the habit of arriving at the most surprising moments. On Thursday midnight, we found out (thanks to Rachel pointing it out) that during our play session of the board game, we misinterpreted some fundamental rules of the game: instead of using all of the season cards, we were supposed to only use 16 of them in total; when a card is drawn, all players would take their actions! Also, players were supposed to collectively share their heart tokens, so the artificial conflict over Jodi wasn’t… supposed to exist?!

Still, this unfortunate misconception did lead us to some reflection on how our interpretation changed the core meaning of the game. When we realized how the game was intended to be played, we almost unanimously agreed that the intended experience of Stardew Valley would more closely resemble that of the video game version:

I guess being stressed about running out of time is just a part of the dev-intended stardew experience.

Rachel (Thursday, 1:55 A.M.)

cozy but with a deadline

Sanaiya (Thursday, 1:55 A.M.)

isn’t that just…taking a break at uchicago

Moreover, it is also very interesting that, despite completely misunderstanding a part of the rules, we kind of made the game our own through our version of the rules. Time being much less of a factor that it should have, the four of us took their absolute bountiful time fishing and selling them for money despite it not being one of Grandpa’s goals, spent countless turns fighting to make friends (ahem, Laura and Sanaiya) at the community center, and always forgot to plant crops and water them despite literally living on a farm. But hey, it was nice and cozy in its own way, and we had a great time in the Valley. Even if the conflict over befriending villagers was not supposed to exist, I believe that all of us had a great time because we made it exist. We had fun.

Isn’t that what matters the most?