I won a series of Fascist victories in Secret Hitler (2016) through largely passive strategies. After the first two rounds, I knew that I was likely to win, and I remained silent until a handful of rounds later, when I was elected Chancellor. While I reflected on those experiences as rather uneventful, my friends seemed thoroughly surprised by my victories. I’m a notoriously bad liar, but they were convinced I was on their side. What led my friends to have such a strong emotional reaction to our games, and why didn’t I feel the same way?

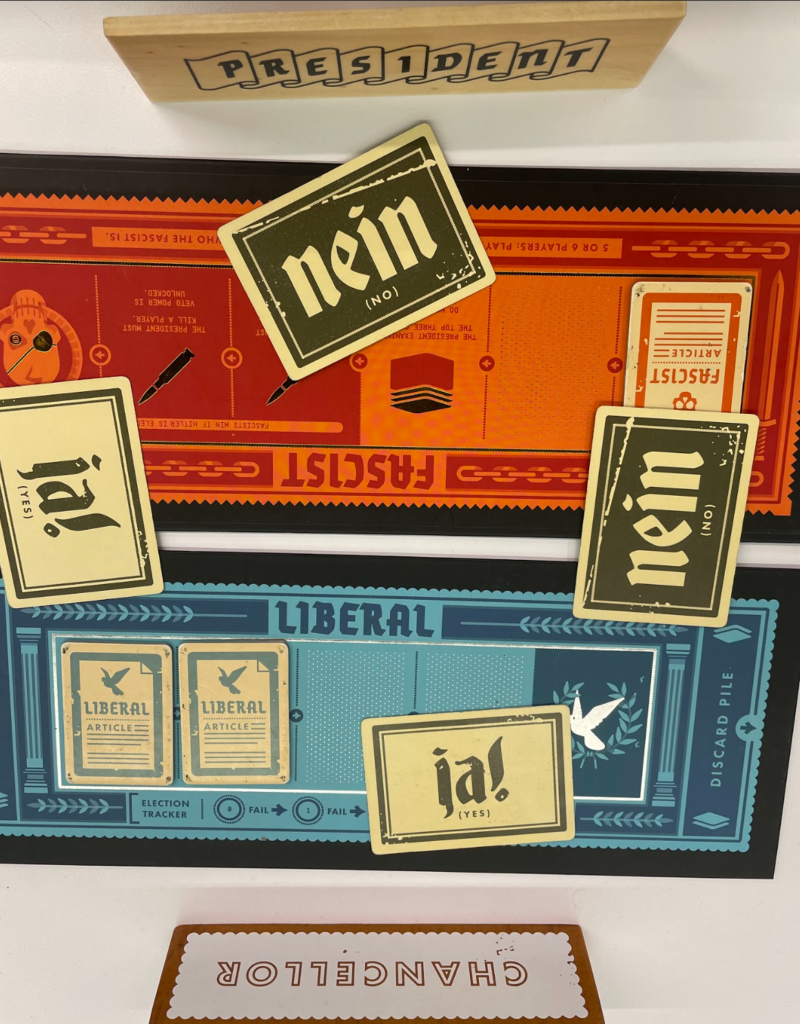

Secret Hitler borrows its mechanics from the hidden identity trope within the social deduction genre. Players are separated into Liberals—representing the majority of the group—and Fascists —representing the minority, one of whom acts as Hitler. Both teams seek to pass a specified number of policies of their team’s alignment through a majority vote, though the Fascist players may additionally win by electing Hitler as Chancellor after enacting three Fascist policies. Operationally, Fascist players know their allies at the start of the game and block policies by eliciting distrust among the Liberal players.

Before examining the diversity of emotional reactions to my game, we must first explore a framework for understanding what causes emotions. The humanistic disciplines distinguish feeling, emotion, and affect. Feelings describe sensations referenced against previous experiences, drawing on personal history to inform a non-falsifiable statement about an individual’s interiority. Emotion captures the methods through which an individual projects their feelings—quite literally, how they emote. Lastly, affect defines the non-conscious experience of identity, existing amid an event.

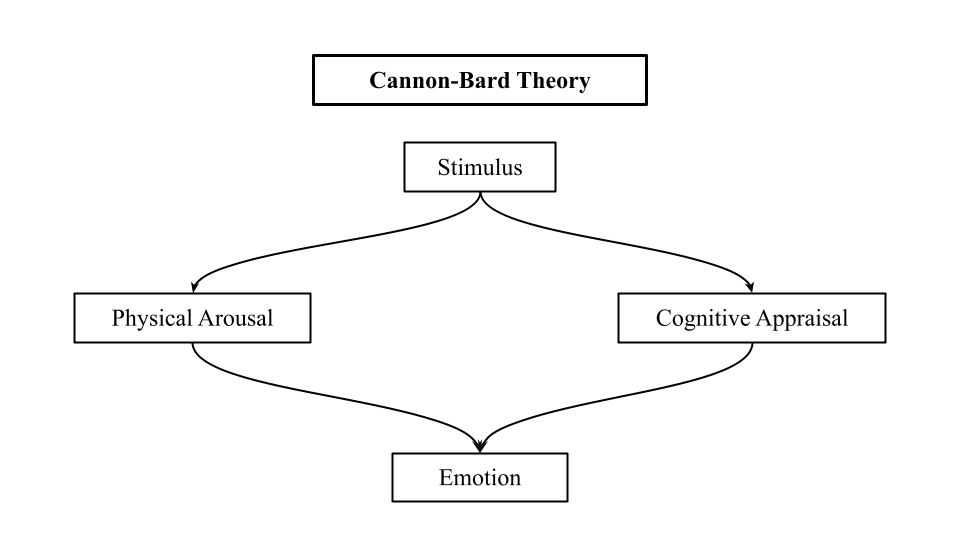

Neuroscientists, however, are more concerned with the mechanisms that produce particular internal states rather than their expression. The Cannon-Bard theory represents one of the oldest frameworks of emotion that remains in conversation within the social and biological sciences. Under this theory, emotion constitutes two factors. Affect describes our bodies’ physical response to a stimulus. Notably, affect is largely subconscious and non-specific; modern theories frame affective states as different degrees of arousal. Consequently, intense emotions—such as love, fear, or excitement—all evoke the same bodily response: increased heart rate, blood flow to the extremities, and sweat production. To differentiate between different emotions, we leverage cognitive appraisal strategies to assess the situation and assign an appropriate label to our physical response. In essence, we use our physical responses to gauge the magnitude of emotion, and our cognitive responses gauge its valence. That’s why it’s so easy to recontextualize anxiety as excitement: they already feel the same, and switching between the two emotions is a matter of cognitive reframing.

Contemporary brain imaging techniques reveal an important extension to the Cannon-Bard Theory: the brain areas involved in physical affective states and cognitive appraisal mechanisms exhibit bidirectional inhibitory connections. The amygdala (physical domain) and prefrontal cortex (cognitive domain) compete for representation: when we keep our affect at bay, more cognitive appraisal strategies come online, and when affective states are too intense, we lose access to those strategies. (For those of you interested in behavioral economics, this relationship maps cleanly onto System 1 and System 2 thinking from Daniel Kahnman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.)

When our cognitive appraisal strategies shut down, our brains are prey to an artillery of psychological tricks, which is where social deduction games derive their voltage. The brain area implicated in the appraisal of emotions also houses our self-regulation and deductive reasoning abilities (similarly, casino games operate through inhibition of this region for more capitalist goals). Players become more reactive and accusatory, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances the game’s perceived stakes. The most salient behavioral outcome that falls out of this feedback loop is called the fundamental attribution error (FAE), which refers to the tendency to attribute an individual’s actions to their personality rather than the situation. The FAE analogizes bleed but applies to interpersonal rather than intrapersonal interactions. I was a trusted friend in my real-world relationships with the other players, and they consequently had trouble assigning maleficence to my actions. In other words, I wasn’t the type of person to play Hitler, even though our roles were randomly assigned. The absence of deductive reasoning skills also forced players to operate primarily on intuition, and as such, they gave significant weight to “tells,” or mannerisms indicating that a player may be lying. I avoided becoming the object of scrutiny by remaining quiet for most of the game, despite passing the highest number of Fascist policies.

The differences in approach between the Fascist and Liberal teams in our games suggest an asymmetry in perceived stakes. The game’s starting conditions elicited a sense of safety for the Fascist team; we had nearly double the number of Liberal policies in the deck and represented 40% of the players. Though the baseline of safety lent itself to emotional escalation as the game progressed, it also trained me to view each round as an extended math problem. Secret Hitler can be played purely based on deductive abilities; unlikely to gauge meaningful information by talking to other players due to the non-negligible probability of being misled. While my Liberal peers were immersed in finding out who was Liberal or Fascist, I was entrenched in the asocial activity of tracking the proportion of Fascist policies in the deck. Though I adopted an effective method of winning, I ultimately felt distanced from the social dynamics at play. How can Secret Hitler nudge Fascist players into an emotional state dominated by affect rather than cognitive strategies? A potential modification to destabilize the Fascist players’ initial advantage may involve a smaller minority of Fascists but more punitive Presidential Powers to elicit a steeper early-game progression. Nonetheless, Secret Hitler holds personal significance, as it validates a neuroscience-informed approach to understanding the player’s emotional responses throughout the game.

References

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Temkin, M., Boxleiter, M., & Maranges, T. (2016). Secret Hitler [Board game].