Unfortunately, the image found further down in this blogpost is the only recording we have of our Dread play session. However, if you were to ask me or any of the other players about our time playing this game, we would say that it was genuinely a memorable experience that genuinely an image would not be able to capture. In that moment we were playing Dread, it felt like we were transported into its world, carefully traversing through as our chances of succeeding slowly dwindled and we approached closer to the impending doom ahead of us.

Designed by Epidiah Ravachol and Nathanial Barmore, this haunting 2005 RPG is a great example of how little is needed to submerge players into a game’s story and world. It leads players to treat this game not as any simple role-playing game but instead one with consequences that we can not only see occur but physically cause, changing the game trajectory for the players when it all eventually comes tumbling down.

The game set-up is quite simple. All you need for a session of Dread are 3-6 players, someone who will serve as a “Game Master” who knows the game’s rules and has an adventure ready, and the iconic Jenga tower. Again, little is needed to play this game and its design is quite minimalistic. However, the manner in which it makes players create their characters and the function the teetering tower serves prove to be pivotal in immersing the players into the game as well as provide a blank slate for future stories to be told.

Similar to many other TTRPGs, Dread itself just consists of a rulebook. Of course you require a Jenga tower to start, but again the entire game is contained within its 99 pages. I’m emphasizing this point to show how not all RPGs – or even arguably board games themselves – need impressive physical components or complex dice-rolling mechanics and systems to provide a successful roleplaying experience. Sometimes all you need is one captivating component to center the whole game around, providing a blank canvas of possibilities.

Here, the pulling of the Jenga pieces represents whether a player succeeds when performing an action during the game. The riskier the action is, the more pieces the player may need to pull, and as the game progresses, it will become harder to get through. Players are allowed to abandon a pull or even refuse to pull, but doing so would result in not only a failure of a task but also consequences for their character. However, the consequences can’t be enough to remove a player from the game. The only way anyone is out of the game is when the tower collapses on their turn, resulting in a fatal end to that character’s story. The only chance where the falling of this tower may prove beneficial is when a player deliberately knocks over the tower, resulting in a succession of a task but the removal of that player.

It’s a quite simple and easy mechanism to understand, yet in the context of the game where having the tower fall means doom for you, you can’t help but feel dread (haha get it?) form within you. Having a physical representation of possible failure in front of you, all relying on one wrong move from your part helps in raising the stakes and sets the tone for the game.

Another factor that contributes to this feeling of this anxiety too comes in the fear of leaving the game. Of course leaving the game would mean you no longer would be able to play which is in general no good, but I believe what turns this into something special is the possibility of losing a character you’re connected with.

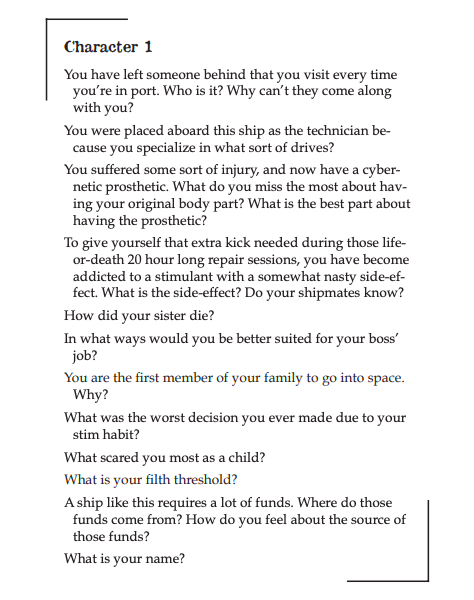

Dread does so with their unique character questionnaire players must fill out beforehand in order to create their character. The questions contained there help not only in establishing who you are as a character, but also build a base for your understanding of this world. This form of character creation proved to be monumental in not only getting players invested in their character but also feeling immersed in the story. It can serve sort-of like a ritual, like the opposite of de-roleing. This process helps players to get into character and begin transitioning into the world, helping think about who they are as a character, how they might play, and get ready to jump into the game.

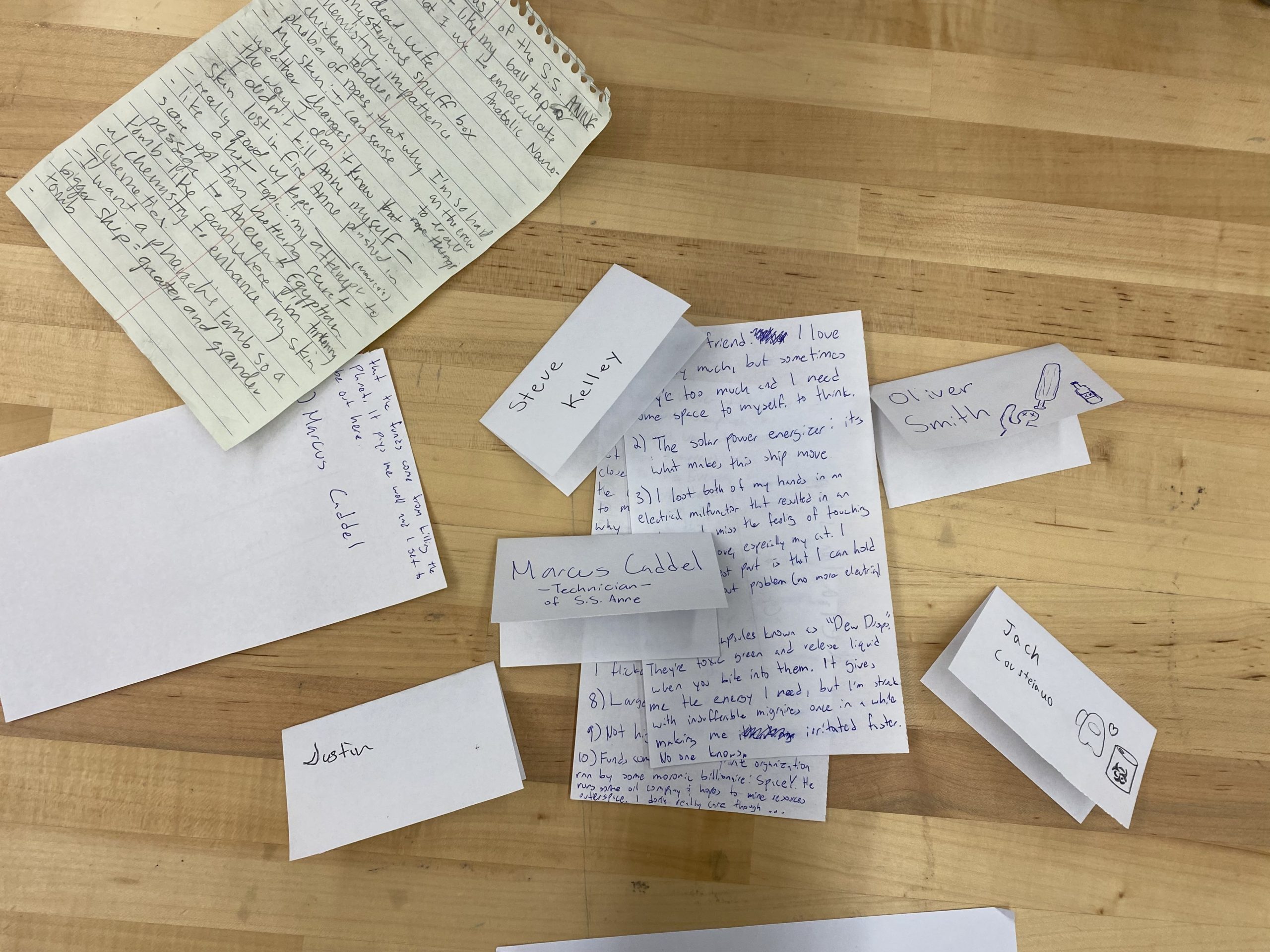

In our play session, we did the story “Beneath the Metal Sky”, and when I was creating my character I was asked deep questions over why I am in space, how I lost a limb, and how as the spaceship’s mechanic, I felt I could run the crew better than my captain. Not only was I able to submerge myself into being this character, but I was able to understand my relationship with other players. For example with the captain, before starting I have made a pre-established relationship and opinion around them which may shape the decisions I take. Also, I was able to include my own personal flair to my character which made me that much more invested in this character and scared to lose them. In the question regarding why I wanted to go to space, I said how I was on a search for my older sister who got lost in a space expedition regarding black holes and while everyone says her and the crew are dead, I still have the hope to find her out there.

Game masters are able to use the responses of their players to spice up the game even more and lead the team through an unforgettable morbid adventure. In addition, with the game’s simple mechanics, Dread is able to become a building base for people to create their own adventures and share their Dread-ful stories with the community! There are countless possibilities for what frightening tales can be told through this RPG, resulting in a game perfect for game nights when players are looking for some entertaining and thoughtful suspense in their session