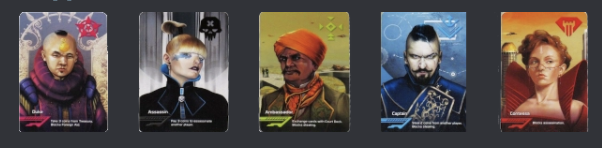

Coup is a game most commonly categorized under the label of social deduction, for the main mechanic that pertains to it is having hidden information in the form of character roles that allow you to take on certain abilities. The game plays out, and players are able to call upon the character abilities of the cards they have; however, they are also able to activate abilities on the characters that they do not possess. This generates the main conflict of the game and epitomizes affective design that centers around paranoia. It is this emotional response that drives player’s actions. The paranoia of whether they will get caught or can catch someone else in a lie fuels this dynamic that nearly begs players to lie if they have any chance of winning the game.

There are clear struggle points in Coup that can be reached to lure out the social deduction aspects of the game. The interesting thing about the design around Coup is that social deduction is crucial not because it is the point of the game, but because it allows players to tip the scales on power struggle scales. One can play an honest game and win; however, there can be clear disparities in hands drawn—like a starting hand of double Contessa—that would be one’s win state in an honest game close to zero. With cards like the Captain, it entices players to simply gauge how much they can lie for once stolen from, you will never stop being the player reaped of your riches.

The magic circle of Coup only truly exists within the analog nature of the game. The physical nature of Coup adds to the social deceit, for like poker, there are often tells of certain people that are near impossible to translate over to a digital format. In the games I played of Coup with the class, I recognized a strange player behavior of simply not looking at one’s cards and playing any character ability they wished. This created an interesting subversion to the game, for if players wanted to call out that this player did not have said card, they would simply just be making a random guess based on their own cards and the revealed ones at the table. This is an inherently negative thing to do, for if you are the player that is making the accusation, you are the one putting your own cards on the line. It is simply a reward for every other player that is not the accuser or the accused; thus, the magic circle of the game is important to keep intact, for variations of play and body language reads are not possible over the digital sphere.

While Coup would be incorrectly labeled if referred to as a roleplaying game, I have always observed different ways players act when presented with their character roles. Oftentimes those who claim to have The Duke will draw from the pile in a greedy way, almost as if they were The Duke himself. It was this behavior—coupled with the fact that it is my roommate Thomas’s favorite game—that had me make a version of Coup with my roommates as each character early in the quarter after playing it for IGD. By making the game physically, I feel it has given me a newfound respect for the functions of what is at play. There is clear intention put both into how players interact with one another that is drawn from the inherent ways the character abilities themselves interact.