In the board game Dixit, 4-6 players are given an assortment of cards. During their turn, each player describes their card briefly, and the rest of the players submit cards that could conceivably also fit the prompt. The players then have to guess which the originally submitted card was, and are rewarded for fooling people; whereas the originator of the prompt only gains points if some, not all or none, players correctly guess.

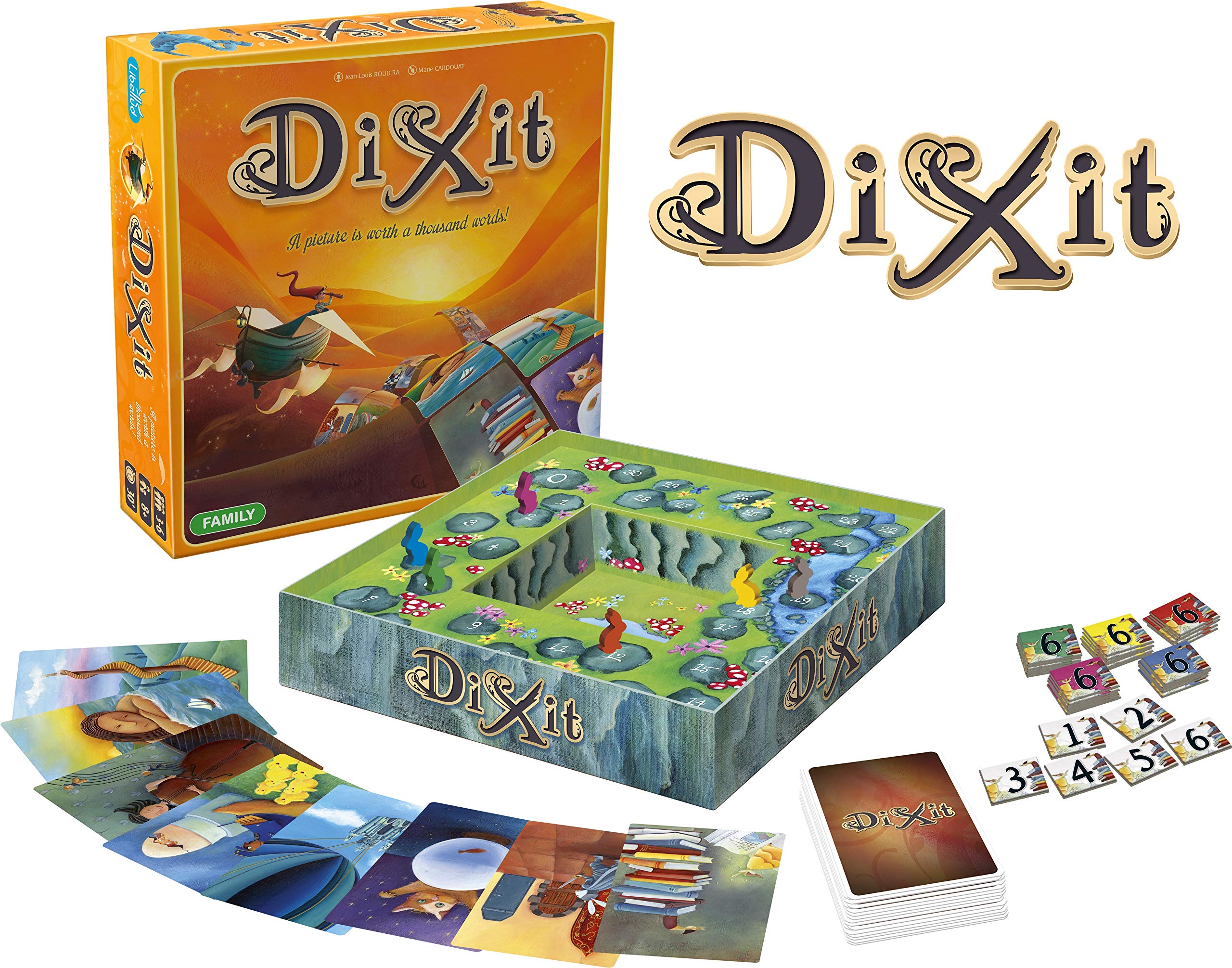

The game is a board game, though the board itself is largely superfluous to the experience- players win by collecting points, which could have been represented through tokens or a scoreboard. This could have been a situation where the design intent was lost on the players, as it seemed like the board didn’t represent anything (like a location, as seen in Monopoly or King of Toyko) and just functioned as a point-keeper without adding any mechanics of its own (such as rules for passing people, or occupying the same square). The accompanying cards, which are designed to inspire the player-generated prompts, were interesting and often had difficult-to-describe images on them, many of which made for intriguing prompts- however, they also sometimes confuse my game partners, who would be unable to create a prompt and would settle on describing a color or small aspect of the scene, which didn’t fit the intended playstyle.

Ultimately, Dixit is a social game about communication, and threading the needle to ensure only part of the group will understand the prompt. The social game was designed for a large amount of player input, as the mechanics support players essentially generating the guessing game. Such a high degree of freedom means that the game depends heavily on the group of people playing it- how familiar they are with one another, and what references they share (as the rules themselves encourage referencing media for prompts). With the way the game is designed, incentivizing having few people understand your prompt, the best way to win would be to target one player in particular, using inside jokes and references to ensure that only one person will understand your prompts and guess correctly. This, however, seems exclusionary and cliquish, not to mention not very fun for anyone involved. I think that restricting the prompt in some way (such as using a particular sentence structure or phrase) would help both in structuring the game (as the other players in my group were often confused or thought for a long time to create a prompt) and in ensuring that players cannot easily derail the game in order to win.

Ultimately, however, playing with people I didn’t know very well worked as intended for the most part, since the issue of specifically-targeted prompts couldn’t have come up. The mechanics resulted in an experience where I had to consider how other people may interpret the image in question, and try to find a concise prompt that was ambiguous enough to work. The game seemed balanced between the guessers and prompt-giver. In our play, we had every outcome (all guessed correctly, none guessed correctly, and some) and everyone was fooled or fooled someone else with a well-placed decoy at some point.