When I pick out a new board game to play with family and friends, I typically pay a fair amount of attention to the aesthetic and theming of the game, finding enjoyment in critically considering the implications that the art style and flavor text might offer to the gameplay experience–as a game studies major, I am a bit embarrassed to say that I, frankly, did not care about any of that when I was first introduced to Dominion. Despite having played countless hours of the game, working on this post was the first time I actually took the time to read through the introduction offered by the game manual, which I now regret overlooking, “You are a monarch, like your parents before you…unlike your parents, however, you have hopes and dreams! You want a bigger and more pleasant kingdom…But wait! It must be something in the air; several other monarchs have had the exact same idea. You must race to get as much of the unclaimed land as possible…Your parents wouldn’t be proud, but your grandparents, on your mother’s side, would be delighted” (1). Framed as a kingdom-building narrative between competing rulers, Dominion is a deck-builder game in which players accumulate new cards to add to their deck, recycle through the cards they have purchased, and ultimately aim to have the most victory points at the end of the game. While the game’s theming opens itself to consider critiques on feudalism and its varied use of art styles leads to questions about how to make cards uniquely recognizable across 15 expansion sets, the aspect of Dominion I would like to focus on for this post is its replayability.

Dominion is a prime example of a game that looks incredibly daunting to learn–a player needs to keep tabs on the multiple stacks of cards that make up a communal purchasing pool, formulate a strategy and recall what cards they have added to their personal deck, all while keeping track of what everyone else is doing on their own turns. Despite all these fluctuating factors, Dominion lends itself to being learned through watching other players. When I was introduced to the game, I was enamored with the skill ramp and strategic depth that the card combinations offered. I suspect it was my fixation on the different kinds of mechanic machines I could build that led to me pass up looking into the theming of the game–I just wanted to read up on what all of the cards would let me do and start playing.

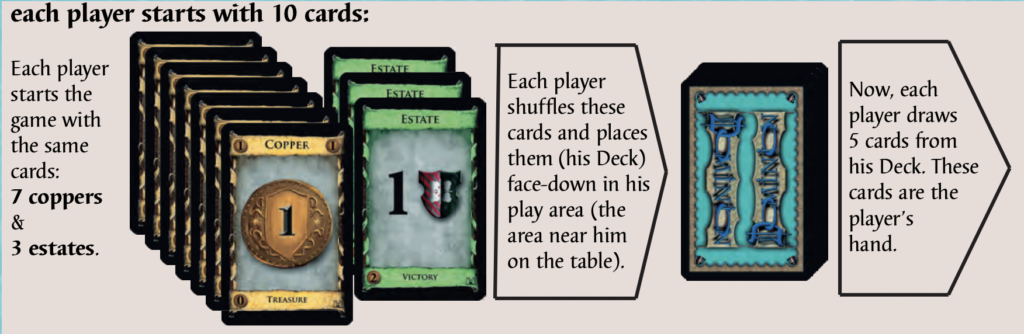

Gameplay begins with each player starting with a deck of 10 cards (3 victory point cards and 7 money cards). In addition to these personal decks, 10 piles of action cards (called “Kingdom Cards”), 3 piles of money of differing values (called “Treasure Cards”), 3 piles of victory cards of differing values (called “Victory Cards”), and 1 pile of “Curse” cards are laid out to make up a communal purchasing pool.

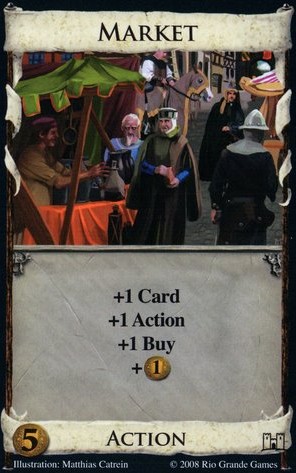

Each player shuffles their basic deck and draws 5 cards from their deck to make up their starting hand for their turn. The game operates on a turn-based system, and on their turn, players go through 3 phases: Action Phase, Buy Phase, and Clean-Up Phase. Each turn, players with start with one Action and one Buy (which can be increased through playing additional Kingdom cards–see fig. 3). Players then play through the action cards in their hand, before deciding whether to buy a card with the money they have accumulated during their turn. The purchased card(s) is then added to their discard pile. At the end of their turn players will discard all the cards they played and all of the remaining cards in their hand, before drawing a new set of 5 cards. Once a player’s deck runs out, they will shuffle their discard pile and begin drawing anew from the shuffled pile.

Players devise deck strategies that optimize their chances of acquiring Provinces, the highest value victory point in the game. The game ends when 3 of any of the communal card piles have been bought out, or when all of the Provinces have been bought. The victory point cards themselves do not provide mechanic usefulness and work to hinder the consistency of a player’s deck. They act as a balancing system such that as a player pulls ahead in the number of points they have accumulated, their deck gradually becomes worse and worse.

The structure of gameplay facilitates player engagement at multiple different scales. At the micro level, Dominion’s limited starting hand size of 5 cards and its ample amount of Kingdom Cards with a draw mechanic tap into feelings of momentum and luck as players eagerly peek at what affordances their next card might offer them. As turns become more complex, players can gain satisfaction in seeing the pieces of their deck engine begin to run smoothly, allowing them to buy Provinces turn after turn, or have a moment of terror when they realize the strategy they hoped to put together never seems to adhere quite as they imagined it. On a broader level, Dominion’s communal card pool orients players to pay attention to what other players are doing–even in a game where there is a lack of interaction cards available for purchase (see Fig. 4). Players are asked to not only consider what strategies they personally want to pursue, but to try and discern what angle their opponents are going for in real-time. This facilitates moments of affect and revelation when realizing a particularly clever scheme another player has put together under your nose. There are also spontaneous moments of collaboration when two players decide to thwart a plan another player is trying to pull off, such as delaying an attempt to end the game early by buying out three card piles. Even when being thoroughly bested by another player’s deck, players can take away knowledge about the winning deck’s engine to replicate when they play next time.

While the learning curve is initially steep, the game entices players to replay the game by making the visibility of what different strategies players develop a central part of the experience. The use of randomizer cards to generate different combinations of 10 Kingdom cards per game offers novel experiences to players, but players are equally welcome to customize certain card combinations they personally enjoy. As certain strategies become more dominant amongst a group of players, counter-strategies emerge creating a rich metagame for players to explore and iterate on. The sprawling universe of Dominion with its 15 expansion sets offers players a wide variety of mechanics to experiment with. Dominion may not offer the more rewarding experience to the first-time player, but its diverse breadth of cards that support a multitude of strategies and playstyles promises the player that if they come back, there is a deck out there just waiting to be built by them.

One critique I would raise about the game is the lack of guidance its rulebook offers to players with regard to keeping track of card sequencing during their turn. Gameplay in Dominion leads to progressively more complicated turns, where players are stringing together multiple Kingdom Card actions that lead to branching opportunities for additional actions. When not given an example of a system for how to lay out or arrange cards during one’s turn, it can become increasingly difficult for players to keep track of how many actions they still have left available to them. I believe including a diagram of a possible layout structure in the rulebook would be beneficial to players and would improve the clarity of play.

An aspect of the rulebook that does have a consistently positive impact on gameplay is the “Kingdom Card Description” section which goes in-depth into edge case rulings on Kingdom Cards and provides detailed examples of how to play out complex scenarios. Since checking these rules can be a frequent occurrence during the game, by including these scenarios in the rulebook, players have easy access to the information while still remaining within the game’s play space, rather than having to resort to looking up the rulings online. Additionally, a side effect of reading through these descriptions is that players can discover interesting strategies offered by the examples that they may not have considered previously.

Lastly, for anyone interested, my favorite house rules variation of playing Dominion is something I call, “The Battle of the Ages.” It is a series of games where players go through the entire Kingdom Card randomizer pool with no repeats. I play this with a mixed blend of Intrigue and Base Set–a total of 50 cards coming out to 5 games. This creates some very unique scenarios to play through, such as games where there are no cards that provide additional actions.

References:

Vaccarino, Donald. “Rules.” Dominion. 2nd Edition. Rio Grande Games, 2016. Print.