For our game analysis, we decided to play ROOT. ROOT is an asymmetric strategy war board game that has resource management, capture/eliminate, and competition game mechanics. It utilizes game pieces, tokens, cards, die, and specific faction sheets to help players complete their actions and work towards their goals. What makes ROOT different from other board games is that each player plays a unique faction, having faction sheets that tell them the order to take their actions, the requirements for crafting or obtaining items, and the ways to gain victory points. There are a lot of different systems at play in this game, and together they form an exciting experience that we ultimately had mixed reviews about.

Game Structure

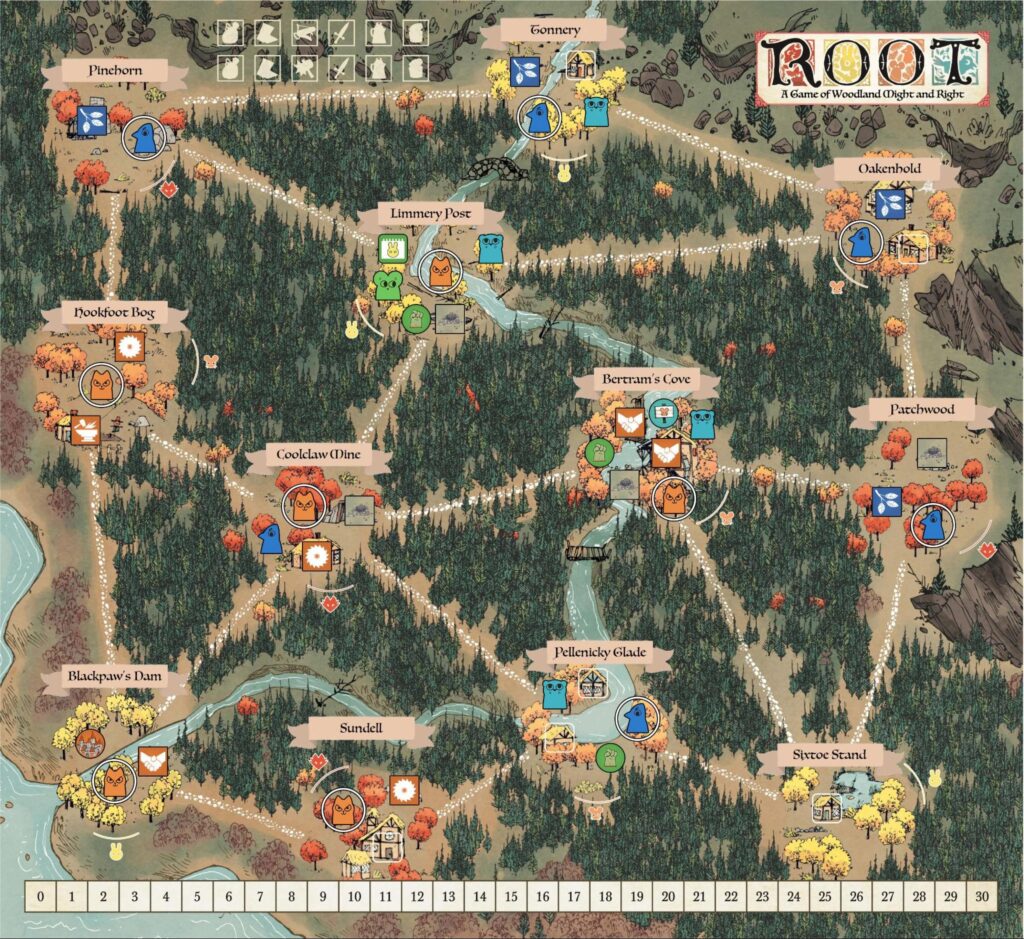

The game is structured around a game board, which depicts a map of the surrounding landscape. The important sections of the map are clearings (labeled with names), paths, and forests. Forests are only accessible to Vagabonds, where they have their starting position or where they go when they are damaged, but they cannot do anything in the Forest. The paths are important because they dictate how your units can move, meaning they cannot jump between clearings. Clearings are the most important pieces on the board. Some factions can use the square blanks in the clearings to build, and other players can enter clearings to try to conquer them or trade for items.

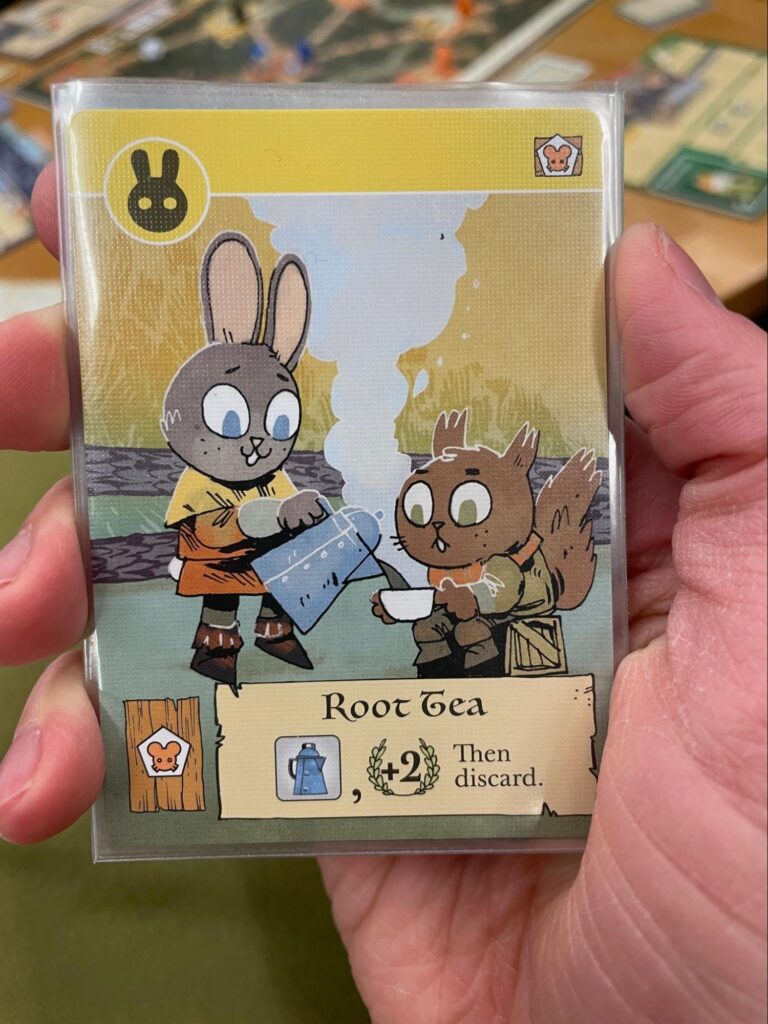

The other pieces in this game are either communal or unique to players. Players themselves have access to their own set of little guys (units), their resource tokens, and their buildings, which their character sheet will tell them how to use. The cards and items are communal; at the end of each player’s turn, they draw a card. Each card means something different for different players, but it generally tells you what it does on the card itself. The effects of the card are also affected by its suit; there are four suits in total: mice, rabbits, foxes, and birds. The mice, rabbits, and foxes correspond to the types of clearings there are, while the bird suit can represent any of the other suits.

Finally, the structure of each round is that each faction takes a turn, which involves doing the actions that are detailed on their character sheet. The goal of a faction’s turn is to score victory points or to set themselves up to score more victory points on their next turn. Some factions’ goals are to fight/destroy other factions, so players need to make sure they protect themselves during their turn too.

This game structure is interesting because there is a lot of setup to the game, but the gameplay itself is easier. Learning the rules and setting up the game was challenging just because of the sheer number of moving parts. Players have to understand all the other parts, but each player only has to manage their moving parts. We spent a lot of time learning the rules, but even after doing all that, we still managed to mess up the rules in certain parts, so we played a sort of homebrew version of ROOT.

Turn Order

The order in which players set up is based on a specific order determined by the developers, but the turn order can go in any order you want (we chose clockwise). The setup order is Marquise, then Eyrie, then Woodland Alliance, then Vagabond, then Second Vagabond then the other factions from the expansions (which we did not play with). This setup order is specifically put in this order because the Eyrie setup kind of depends on where the Marquise sets up their headquarters (called the Keep). Then, the Alliance sets up by getting cards as supporters and planning out where they will start gaining support based on the state of the map. Then, the Vagabonds choose which forest to start in based on the state of the map. The way the game starts is very important to the game, as where you start can determine what sort of crafting, what types of items, or what kind of units you encounter.

Factions

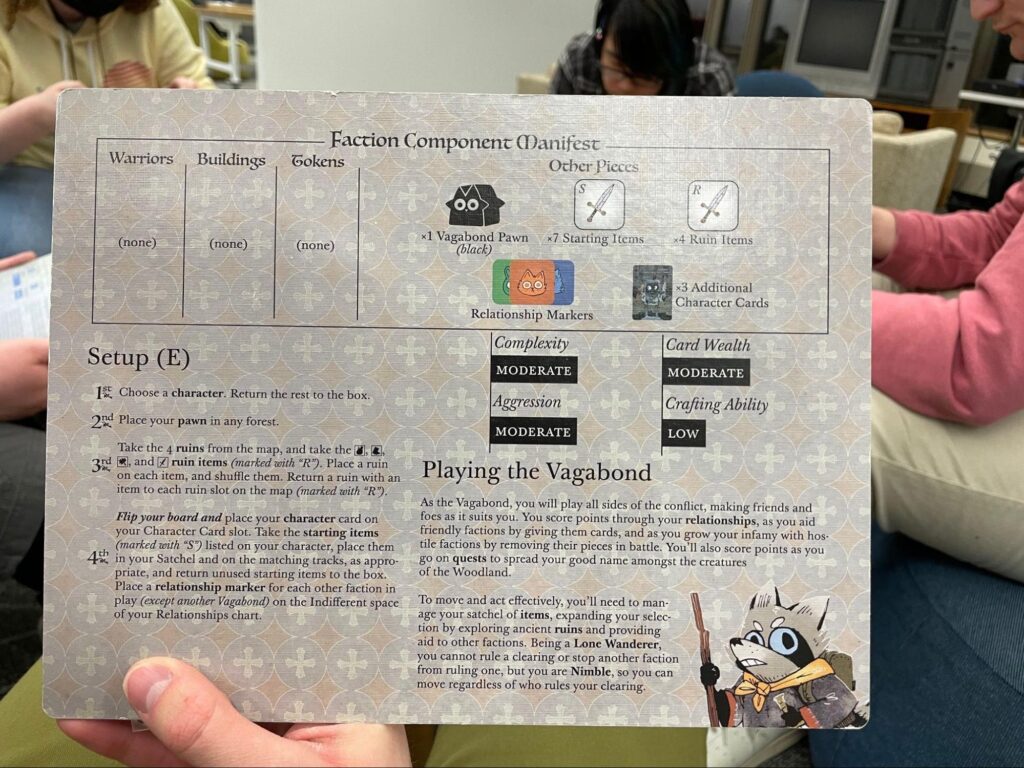

In our version of ROOT, there were 5 factions. Jamie played the Marquise de Cat faction, which was technically the antagonist of the world lore. The goal of the Marquise de Cat is to build buildings and expand the Cat Empire. The Cat’s main enemies are the Eyrie Dynasty, which was played by Matt. The most important aspect of the Eyries is that they must follow a decree based on a random leader unit. The goal of the Eyries is to build roosts and follow their decree, or they will lose all their victory points and have to start over with a different leader. An enemy of both the Cats and the Eyrie is the Woodland Alliance, played by Ben A. The Alliance’s goal is to start revolutions and establish a grass-roots governance of the oppressed (the foxes, rabbits, and mice). They do this by gaining sympathy for the cause in different clearings, then using it to build headquarters and fight the others’ units. The final faction in our game was two Vagabonds, played by Jude and Ben B. The Vagabond is sort of like a general civil servant, traveling around the map and gaining victory points by helping other factions. If the Vagabond determines that one faction has a bigger advantage, then they may form an alliance, and if either the Vagabond gains enough victory points or if the faction they are allied with wins, then the Vagabond wins the games.

There were a lot of complexities in the factions, and it was very difficult to understand some of the rules surrounding them. For example, the Eyrie faction introduced several new and ambitious game mechanics, but more often than not it leads to no-win situations that destroy their standing in the game. It seems like the only way the Eyrie player has a chance of winning is by playing a Dominance card. In addition, it felt like the game was not initially designed with two Vagabonds in mind. There just didn’t seem to be enough items for both Vagabonds, and they ended up competing against one another more so than the other players. After we finished playing, we concluded that if you took vagabonds out of the game entirely, functionally nothing would change.

Actions

On a faction’s turn, three phases correspond with actions the faction can take. In the Birdsong stage, the player takes an action that sets them up later to earn victory points by generating resources or moving the player towards resources. For example, the Cats can generate wood during Birdsong, which they will later use to build buildings. The Eyrie on the other hand can add a card to their decree, giving them more action opportunities. The next phase is the Daytime phase, where the bulk of a faction’s actions are made. These include crafting, exploring, attacking, building, and trading. These actions are determined by the character sheet and are designed to give the faction an advantage or victory points. Finally, the Evening phase makes the faction resolve whatever leftover actions they have and draw a card to have a maximum of five cards.

Because the actions are specific to each player, they were easily the most complex and confusing part of it. The rules sometimes used confusing vocabulary to talk about the actions such as using both “refresh” and “repair” to talk about the Vagabond being able to flip over their item token so they can use it again. The Cat’s rules also talked about “activating” workshops which didn’t make any sense, and Jamie had to look it up to understand what it meant. The Eyrie actions were the most confusing because if they ever created a situation for themselves where they couldn’t fulfill one of the actions that they have to because of their decree, like when Matt didn’t conquer a clearing so he could not build a roost, they lost their decree and all their victory points. There didn’t seem to be any advantage to playing the Eyrie faction at all because of this complexity. It seemed that the Eyrie role required cycling through leaders and keeping everyone at bay so they could draw a Dominance card and win.

Another aspect of the actions was the cards. There was a communal deck of cards face down that each faction drew from, and their faction sheet would tell the player how to use the cards. The Woodland Alliance, for example, could either use the crafting cards to craft items, use the cards as supporters so that they can place sympathy tokens, or keep the cards to be played later, like the Ambush card. Just like the actions, the way cards are used is specific to each faction. The Vagabond factions also had their deck of cards that only contained Quest cards. Quest cards were the Vagabond’s primary ways of getting victory points, and each quest requires the Vagabond to be in a specific clearing (either a fox, rabbit, or mouse clearing) and have specific items. This was bad for Jude, who needed a tea item to complete any of their quests, which meant that they could hardly get any victory points until they got a Tea item, especially since Ben B. started hogging the three tea items that were already in play.

Resolution

During each faction’s turn, they have the opportunity to create conflict or create relationships. For example, Matt’s Eyries took every opportunity to battle Jamie’s Cats on his turn because he needed the space to build Roosts. These conflicts are resolved using 2 d12 dice, with 3 sides of numbers 0-3. The two opposing sides of the conflict each take the d12 and roll, and the number on the die is the number of units they damage. This was a very satisfying version of conflict resolution because there was a chance that the enemy did not do any damage to you but you did damage to the enemy. It also was interesting that you could do battle against buildings so that you could remove an enemy’s building and replace it with your own. There was also a built-in mechanic to the Woodland Alliance where battling a Sympathy token would destroy the number of units of the highest roll in the two rolls, so it was generally bad for any faction to try to defeat the Woodland Alliances. Otherwise, the resource management part of the game made it so factions should prioritize protecting their resources rather than being on the offensive unless they were playing the Eyries.

Game end/Victory

While our playthrough was not long enough for one faction to win, the win condition is usually obtaining 30 victory points. Otherwise, if a player has a Dominance card in their hand and has at least 10 points, they can play a Dominance card to create an alternate win condition that any of the players could achieve. It was generally advantageous to only play a Dominance card if you already reached the win condition or almost reached it. Each player generated their victory points using either cards, which gave victory points written on the cards themselves, or by completing tasks from their faction sheet. It was also possible to prevent players from winning. For example, if the Cat’s keep is destroyed, the Cats can no longer do anything and therefore cannot play the game (and therefore cannot win). If a Vagabond hogged items that the other Vagabond needs, then they can prevent the other Vagabond from winning as well. There is a lot of strategy involved with gaining victory points and preventing others from getting them.

Uncertainty

The points of uncertainty in ROOT come from drawing cards, rolling dice, and anticipating the other factions’ moves. Because you never knew what card you could draw, it was always a point of uncertainty. Drawing a bad card could never hurt the player though, because cards can regularly be sacrificed/traded to gain units or items. Rolling dice were only used for battle, but the battle is an important action that could determine your strategy moving forward. Finally, anticipating the other factions’ moves led to uncertainty because they could target you and ruin your plans. The uncertainty in ROOT was not as important as the resource management and strategy parts of the game, but it felt good to let certain moments be strictly up to randomness, like in battles.

Economics/Resource Management

Different resources are important to each faction. For Cats, wood is an important resource. For the Woodland Alliance, the supporters are the most important resource. For Vagabonds, items are the most important resource. For Eyrie, the bird units and cards that are added to the decree are equally important resources. Each faction was focused on managing its own resources gaining victory points AND fending off the other factions. This combination created a lot of opportunities and a lot of potential strategies to try to stay afloat. Generating resources were often given from the Birdsong phase in each faction’s turn. The strategies themselves came from utilizing those resources to place things onto the board. For example, Vagabonds could excavate items from Ruins, but after all the Ruins are explored, the only way to get them is to hope that a faction close to you crafts that item. This could be coerced by giving a crating card of that item to a faction close to you. Once you can get that item by trading for it, you can finally use it to complete quests and earn victory points. This sort of resource management is unique to the Vagabond, but it still has the same flavor as the resource management of other factions. A big part of it is hoping that other factions enable you to generate more resources, but otherwise, the factions have their own goals in terms of management.

How this applies to us

We concluded that ROOT is above the scope of the board game we want to make. The game mechanics that we liked from this are that every faction has a way they can ramp up victory points. But the factions aren’t necessarily only playing by themselves, they have to interact with the other factions to enable their victory. There are also multiple ways to earn victory points for each faction, including the cards, the actions, and relationships (alliances, battles). Choosing a faction means you have a huge amount of customization, since factions have very different mechanics. They all interact with cards differently, so they have different ways to score victory points. And even though we never played it, the Domination/Dominance cards were an interesting way to present an alternate win condition for factions that found it hard to gain victory points.

Game mechanics we didn’t like included the entire Eyrie class, which was entirely too disadvantageous and complex for a player, especially, a beginner player, to win with the faction. The Vagabond classes also seemed entirely unnecessary to the game. Not only were items extremely limited, making it difficult for two Vagabonds to exist wtithout basically blocking the other from winning, but the items were randomly crafted from cards in the deck, meaning it could be a while before a crafting card is not only drawn but crafted. Finally, the rules were a bit unclear, to the point that we read the rules and thought we understood everything, but still ended up having questions and playing the game wrong.

All in all, ROOT was an interesting experience, but we don’t think we’ll take a lot of the mechanics to our board game. We do, however, like the idea of each player playing the game in their own way. The idea of the abilities being common between all factions, but the requirements to do them differ between them, is interesting and possibly something we’d like to do as well.