Coup is a social deduction game in which players hold two cards that grant them certain abilities. These abilities include variations of gathering/stealing coins, assassinating opponents’ cards, and blocking opponents’ moves. What’s special about Coup is that players can lie about what cards they have, allowing them to take any action… so long as no one successfully calls their bluff.

Overall, I found Coup to be really fun. Keyword being “found,” but more on that later. The bluffing aspect was scary at first, but—perhaps concerningly—lying with confidence is a skill one can pick up on pretty quickly within the magic circle of a game where morals aren’t encouraged. Or, in my case, being so baseline unconfident that everyone always thinks I’m lying when I’m not, and using that to my advantage. Overall, Coup is good at creating a fun social environment as players try to simultaneously gain trust with, betray, and generally psyche out their opponents.

When a player takes an action, any other player is allowed to contest their move. Of course, the contesting player puts themselves at risk in the process—if the contested move was in fact valid, the player who contested that move loses a card. This mechanic forces players to weigh their confidence in their reading of opponents’ bluffs, as well as their positions. I find it a bit odd that anyone is allowed to contest, as it requires one player to put themselves at risk. It’s always more advantageous to sit back and hope someone else contests, unless the player contesting has no other hope of winning. Without a direct reward to the contesting player, this mechanic does not align with the game’s theme of being a selfish backstabber.

In my experience though, contesting is not the main issue with Coup. For me, the main issue with Coup is that my friends and I played it way too damn much. In 2019, it became a staple of my house’s culture so fundamental that— upon hearing the word that we all had to go home, I made a Discord bot to let us play Coup remotely.

This oversaturation of Coup was its own downfall amongst my house friends. We learned that, with sufficient experience, the gameplay changes drastically in nature from a social game to a puzzle game.

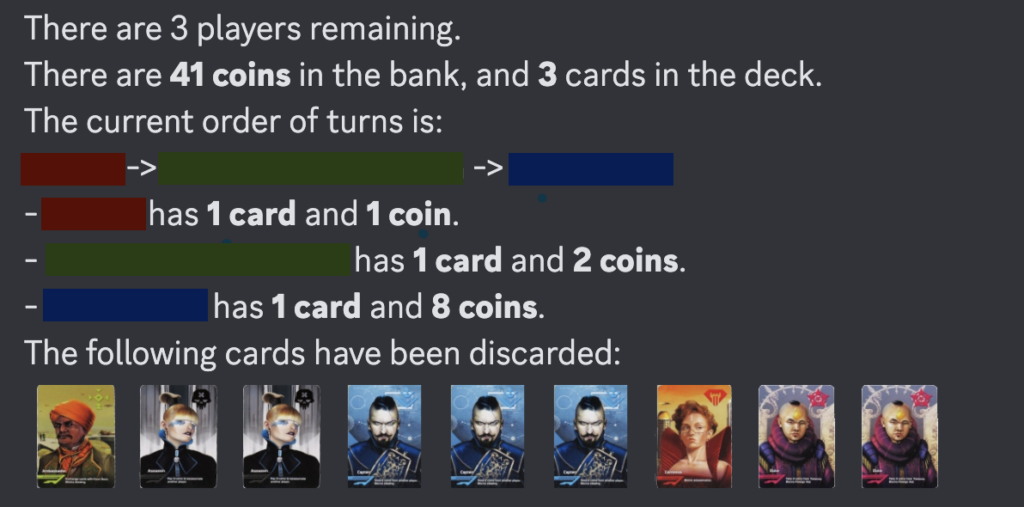

The small number of cards in Coup means that, in later stages of the game, it’s possible for players to keep track of who has what cards and the likelihoods of players having certain cards. Essentially, the low number of cards in a deck means that players can “count cards” without too much effort, thereby stifling or sometimes completely removing the social deduction that makes Coup what it is.

A completely different strategy I’ve seen employed is to simply not look at your cards at all. This of course comes with major disadvantages: you don’t know what moves you can take safely, and you have less information on other players’ cards. However, it also breaks the essence of the game itself: bluffing is no longer valid, once again removing the social aspect of the game and reducing it to a problem of math and memorization.

If there’s a lesson to be learned from all of this, it’s the following: When it comes to social games, it’s probably best to not prioritize winning.