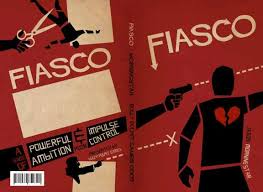

FIASCO is a chaotic TTRPG system in which players create complex relationships between each other and their setting, then construct and act out scenarios with their characters. The game consists of a character-selection and relationship-creation phase, then a scenario-acting scene through which the story progresses – a twist phase in the middle of this section creates a sudden change to the direction of the story. FIASCO involves players not just in the construction of a narrative through gameplay, but in the establishment of the rules of play and the space in which they interact – this process is both a naturally emergent result of play and an explicit function of FIASCO’s rules of play. Through this structured form of involvement of the player, FIASCO not only encourages but requires player-built rules of engagement, and conveys that storymaking is an inherently social process defined by the interactions between people as both storytellers and listeners.

The first phase of a FIASCO game is character creation and selection of details like relationships between characters. Players roll dice to select details and relationships from a predetermined list that can be either provided by the game or constructed by the players for a customizable experience. While the options and structure for this process are provided by the game, the actual development of the narrative premise originates from the player discussions that occur in this section. Players exclaim and gleefully discuss humorous potential stories as they roll new details: for example, when my group rolled for a drug dealer relationship, we came up with ideas about how one of the players who was already the father of another might have become alienated from his child because of a drug addiction encouraged by his dealer. This process occurs naturally from player tendencies to discuss, but it is also a well-defined intended mechanic of FIASCO: the rules state this intention and attempt to establish a conversational tone to encourage this (although the effectiveness of the rulebook’s execution of this conversational tone is debatable). Often games create the potential for emergent narratives by offering a space in which they can occur, or various details like objectives or NPCs that players can interact with; FIASCO, however, directly involves the players in the construction of the setting from which emergent narratives occur. Furthermore, this involvement isn’t a surface-level selection of preset options – the most important aspect of the first phase of FIASCO is the discussion and creation of a mood, relationships, and direction of the narrative, rather than rolling for predetermined details.

The remainder of FIASCO consists of playing through the narrative that has been constructed in the first phase. This section is also player-driven in a more nuanced way than just interacting within a preconstructed space: the mood, events, and outcome of each scene are directed by player choices and specifically by interactions between players. In each scene, the rules define a mechanic by which either the scene premise or outcome is determined specifically by improvised decisions between the entire table of players – in this way, the narrative is decided not just by players’ desires but the unique details of their social interactions within and without the space of the game’s events. This phase, however, felt less important in my experience of play than the initial phase, despite taking up the majority of the play time. The first phase was important because of its player-driven construction of gameplay, and it felt like a unique modification of the ritual of entering play in which the ritual was an extended gameplay process itself. It still felt like it embodied a liminal space in which we, as players, still did not fully know our characters or where the game would go – however, we were immersed in gameplay because the construction of characters and their spoken and unspoken details was a gameplay process and not an extraneous thing done as a chore outside of play. The process of assembling the social contract of play was done inside of the magic circle of play – I’m not sure if this is a perfect analogy, but this is how I understood the experience as I played it. Not only was this liminal space a crucial aspect of the play process, it felt like the central aspect of it – the rest of play was just an enactment and limited exploration of the results of this construction.

From a design perspective, this process creates a generally fun play experience with a unique affective social space – from a more literary analysis point of view, however, it constructs a message of stories as a social interaction rather than a self-contained medium. Although the procedural rhetoric vs. play-centrism argument has limited use as a partisan viewpoint rather than a point of generative discussion, some of the concepts forwarded by play-centrism are very applicable to the gameplay of FIASCO. The game does not simply provide a space for players to create emergent narratives and find meaning through their play; it explicitly involves players in the process of construction of the game and narrative as a game process itself. The meaning of the story and experience of play emerges not from playing through the world created, but through the social process of creating the world itself, building off of each other’s ideas and constructed characters in a liminal space of building a world and being partially entered into it but not entirely. This reflects how stories, by one argument, do not derive their meaning from their contents and events, nor even from how audiences interpret and experience them individually; instead, their meaning arises from the interaction between people acting as both tellers and audiences, constructing unspoken narratives from their interactions as they construct surface-level acknowledged narratives.