Hello, I’m Jacob Wilson.

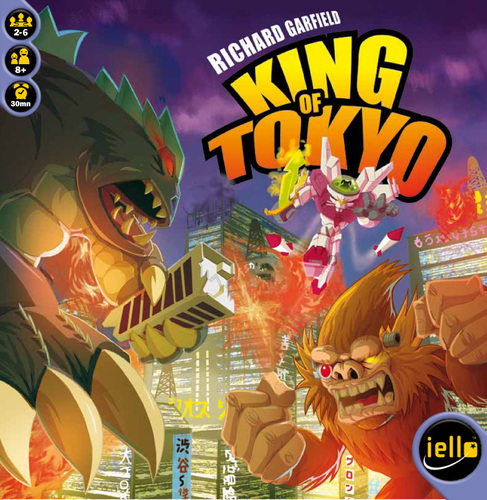

I’ve probably played more complex games in my life than King of Tokyo, but I found it to be thought-provoking and enjoyable in unexpected ways. The premise is simple: you’re a big monster (my favorite is Space Penguin) trying to dominate Tokyo either through accumulating victory points by remaining in the city, or by eliminating your opponents. I don’t often play board games, so some of this may seem obvious to more seasoned veterans, but I nevertheless found playing the game to be a good learning experience in game design. The inherent concepts are simple but expanded upon in ways that feels natural and add great depth- the kind of game that is easy to learn but hard to master.

There are three aspects that I found interesting, the first being the game’s use of dice rolls, the second being the depth of the game’s strategy in spite of the simple premise and simple selection of actions, and the third being the concision of the game’s manual.

Dice rolls are integral to King of Tokyo, but not in a way that necessarily makes the player’s experience based purely on randomness. The dice rolls in each turn allow you to perform four potential actions at once: either attack other monsters, heal your wounds, acquire currency to buy cards that grant special bonuses, or earn points. These rolls do not necessarily doom you to failure, though, as you are allowed to re-roll dice of your choice to facilitate your strategy whether you choose the route of violence or the route of point-earning. This adds an enjoyable layer of complexity and tension – as someone who likes action-packed games, I found myself choosing the violent route, but the fact that I would not always succeed lead to more outcomes than would be possible if my stubborn insistence on aggression were not mediated by randomness. The same can be said regarding my friend’s strategy, which was to acquire points and try to negate my attacks through special cards. He did not always succeed either. Though I have not played enough rounds to be certain, I would expect that the additional uncertainty of outcomes brought about by dice adds more replayability.

In attacking monsters, additional strategic complexity emerges in the fact that you cannot attack monsters in the same place as you – a monster outside of Tokyo or in a different part of it may try to force the other out through continued violence and then begin to earn points itself. Were this rule not in place, it would be far too easy to be both the aggressor and the point earner, as there would be no reason to specialize in one role or the other. The use of small numbers and physical representations of said numbers (small green cubes to represent currency and character cards with wheels you can spin to show different point numbers) keeps the mathematical aspect of the game unobtrusive.

I have not gone into extreme specifics, but I would imagine that you, the reader, now have a solid understanding of the game. I feel that the manual functions in a similar way. There is inherent complexity to the mechanics, and yet the manual is comparatively short and does not spell things out word for word. I found myself wondering things like: “Can I, or must I take this action even if the manual doesn’t say so? Must I try to enter the city if I’m outside of it? Oh, I don’t. Nice.” Some more clarity in the manual would have probably made for a speedier, less paranoia-inducing game experience for me, but at the same time, I feel that I understand the game’s rules well. Perhaps I understand the rules better solely because I had to deduce them, and other players may consider obvious the things I had to deliberate on and thus get into the game more quickly with less unnecessary reading. Thus, it’d seem that this game’s concise manual is a double-edged sword, and one where the two blades are balanced in length. To compare something to a double-edged sword is often a criticism, but in this case, I would consider it to be a good double-edged sword – a well-written manual.

Conversely, I found myself drowning in the long manual for the Street Fighter deck-building game. It’s more abstract than a round of any of the Street Fighter video games, so its increased length relative to something like King of Tokyo is understandable… and yet I was so confused I could hardly even get through my first turn. Perhaps if I had played a deck-building game before Street Fighter, I’d be able to play it, but because the explanations are so focused on the game’s specific mechanics rather than those broadly found in the genre, I would expect other players that are unfamiliar with deck-building games to be similarly confused. Were I compare this game’s manual to a sword, it’d be Excalibur. And I, unfortunately, would not be King Arthur. Only the chosen ones can pull it out of the pedestal!

Having said all that, I have no choice but to conclude that King of Tokyo is a well-designed game!