Love Letter is a 2-6 player card game where you’re incentivized to deduce the cards that other players have in their hands. While this is a feeling common in many card games, especially social deduction games, I haven’t played a game that encouraged deduction to this degree via a deck. Many games encourage you to deduce a permanent role or single card of another player, but this one uses traditional drawing mechanics to incentivize deduction not just of other players, but the deck itself. So, I would first like to explore the rules and mechanics that encourage such gameplay.

Gameplay

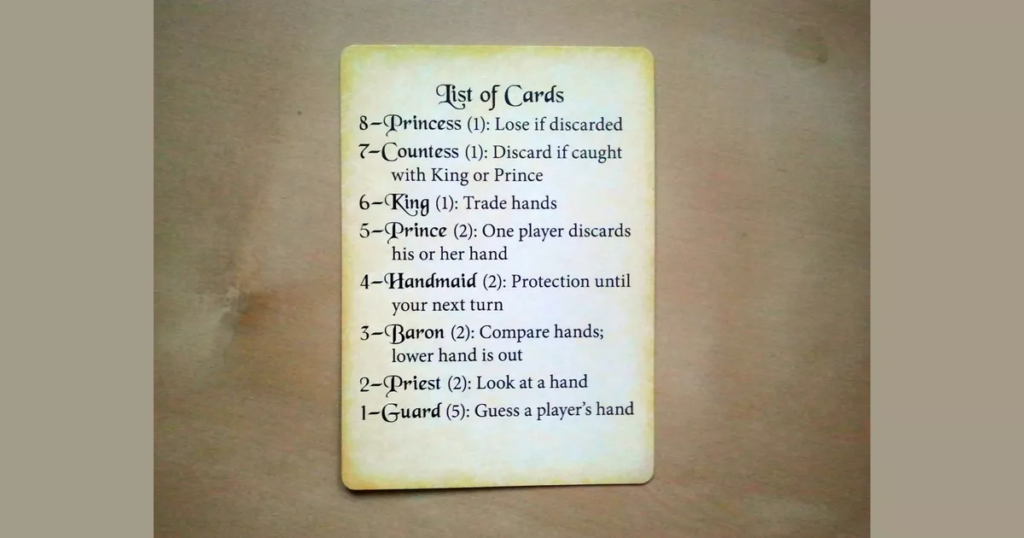

The goal and mechanics sound very simple. Your goal for each round is to have the card with the largest number at the end of the round or make all other players discard their cards so you’re the last one left. The gameplay loop involves each player drawing a card and choosing to play one, so they only ever have one card in their hand during another player’s turn.

Looking at the rulebook alone, it seems that the only mechanics players may use are drawing and playing cards. Of course, these cards have unique effects, which will be discussed more later. However, even without those effects, there is another action that the game implicitly encourages the player to engage with. This is the action of deducing what cards other players have. As the game progresses, players will thin out the deck by playing and discarding cards. Since there are only 16 cards in the deck it’s not too difficult to figure out which cards are left in the game, and therefore, which cards others can possibly have.

Love Letter encourages this behavior with a few components and rules. Its most notable component to this end is a small cheat sheet that reminds players how many of each card are in the deck at the start. As for rules, the most important ones are the relatively low deck size and the rules that all played and discarded cards must be left face-up in front of players. So at any point during the game, players are easily able to calculate the cards left in the deck.

Calculation and Deduction

However, that word, “calculate,” can sometimes lead to moments where it feels like a player has put a pause on the game to do the math. There was one particular moment I remember where another player took a minute or two to try to figure out what could be left in the deck and our hands. Since I was following along with enthusiasm, I didn’t feel it was much of a problem, but another player seemed pretty bored from it. While brief, I would imagine that this element of counting the possibilities might lose the interest of some players.

Personally, I usually find calculations in games to feel boring even if I know it can make gameplay more optimal. I think about certain strategy board games where combat is very deterministic, or some RPGs where you might spend time optimizing a build on paper. There are certainly players who this appeals to, but I don’t consider myself to be one of them.

However, I found myself very engaged with the “calculation” sections of this game. I think this is in large part because of the elements of uncertainty that the game’s rules add. One such rule is that the top card of the deck is removed from play face-down at the start of the round. So even if there are only a few cards left in the deck to figure out, you can’t be certain that you know every card in the deck. Another is that you never get to see other players’ hands unless you use certain card effects, which are rare, or the round is already over. So, while you may be able to narrow down the cards left in the deck and players’ hands, you still have to deduce which of those are in players’ hands.

This aspect of deduction is similar to what you would expect in social deduction games. It may include paying attention to what someone says, like do they ever assume that a certain card is not in the deck because it’s in their hand, or by observing their actions, such as if they keep playing low-value cards that don’t benefit them, which might suggest they are holding onto a high-value card. Naturally, the many factors that go into deduction lead it to be an action with unreliable chances of success, so it adds an element of uncertainty to the game that simultaneously feels somewhat skill-based.

These elements of uncertainty affect gameplay in two major ways. Firstly, it alleviates pressure off of calculations, because you can’t be 100% sure you’re right either way. This feeling is also supported by the short length of each round, so even if we made a math error, it wouldn’t feel like a big deal. Secondly, it makes the outcome and the path leading up to it mostly unpredictable, making the game more replayable and engaging.

Of course, another major source of uncertainty comes from card draw, but I think this should probably go in its own section.

Cards

It might be an interesting experiment to see how this game works without any card effects, but I would imagine it would be much slower paced and less engaging. While players could still calculate and deduce the remaining cards, they would have far fewer clues and tools to help them do so.

Much of the interesting decision-making comes from card effects. Some allow you to see another player’s card, discard someone’s card, swap hands, or other similar actions. These actions of course support the ability to figure out what’s left in the deck by providing information.

Generally, cards with stronger effects have higher values. As a reminder, the player with the highest value card at the end of the round wins, so players are led to balance the benefits of using the card’s strong effect against the drawbacks of losing a strong card.

This characteristic of cards also improves the ability of other players to deduce what others have. As mentioned in the previous section, you may figure out someone has a high-value card if they keep playing low-value ones without hesitation. An extreme case of this is when someone has the princess card, which causes the player to lose the round when played. If a player seems to repeatedly play cards with little benefit quickly, then they may have the princess card.

In addition to adding tools for player’s deduction, several card effects offer ways to capitalize on your predictions by swapping for a better hand or making someone discard a strong card. The guard is the most notable of these cards. There are 5 of them in the deck while there are 2 or 1 of most other cards, so the guard action is meant to occur often. It allows you to name the card in a player’s hand, and if you’re correct, that player loses the round. This is the greatest and most direct payout you get from figuring out what someone has.

Leaving the ability to benefit from your predictions to certain card effects also makes it so you’re not guaranteed to be able to do anything with your deductions. There were some instances where I knew what someone had in their hand, but didn’t have a guard or something else that allowed me to take advantage of this knowledge.

Of course, this adds uncertainty, making it so you have a chance to stay in the round even if someone else has seen your card. This uncertainty also adds anticipation when you know what someone’s card is. It’s not just a matter of “I figured it out, now I win,” but becomes greater excitement when you figure it out and were holding onto a useful card for this moment or you happen to draw one.

However, there were a few times, near the end of rounds especially, where I would figure out what someone’s card is, but not draw the right card to benefit from what I know. These moments felt somewhat disappointing or frustrating, but these feeling are of course diminished with how rare these moments are and how short the rounds are anyway. I don’t think the game would be better overall if the guard effect could be consistently used without need for a certain card, but I think it’s worth noting that delegating certain crucial actions to card effects can lead to frustration when these cards are not drawn at the right time.

Narrative

I don’t think games have to have gameplay that conveys their narrative well, but I appreciate it when they do. I find ludonarrative enjoyable to think about since interactivity is a storytelling tool that few other mediums have. So, I’ll briefly talk about how this game’s narrative is told through gameplay.

Except, I’m still trying to figure that out myself. The gameplay loop doesn’t communicate a clear story. The context you’re given is that each player is trying to deliver their love letter to the princess. Your current card represents who in the castle is currently holding onto your letter. Upon googling some clarifications for the sake of writing this, I think there is a sensical connection between gameplay and narrative if you’re willing to do some slight mental gymnastics.

Still, I don’t think the gameplay conveys this narrative well. It may be because of the lack of components or flavor text, but I never interpreted drawing a new card as passing along the letter, especially since I’m not sure why there couldn’t be a single person who delivers the message the whole way.

However, as I kept thinking about the game after playing, I realized that there is actually a very strong harmony between the affects of the player and those of the characters. The light-hearted yet frantic attempt to figure out what others have in their hands mirrors the somewhat low-stakes yet big-deal drama that would sweep a castle when they hear rumors about a love letter sent to the princess. Just as we are looking at cards and making predictions to figure out the identity of another player’s hand, the townspeople are likely snooping around and gossiping to determine the identity of the suitor. Personally, I think putting the player in a character’s shoes emotionally is more impressive than conveying a literal narrative clearly.

Closing

Overall, Love Letter kept me engaged as every card played gave me new information for what cards could be left. While I played with 3 and enjoyed it, it seems better with a larger group as this would lead to a distribution of cards that give players more information to consider. If you want a short experience that rewards you for paying attention to each turn, this would be a great game to choose.