Annaliese Vorhees, Jason Frey, Steph Chung, Erin Matthews, Ben Sim

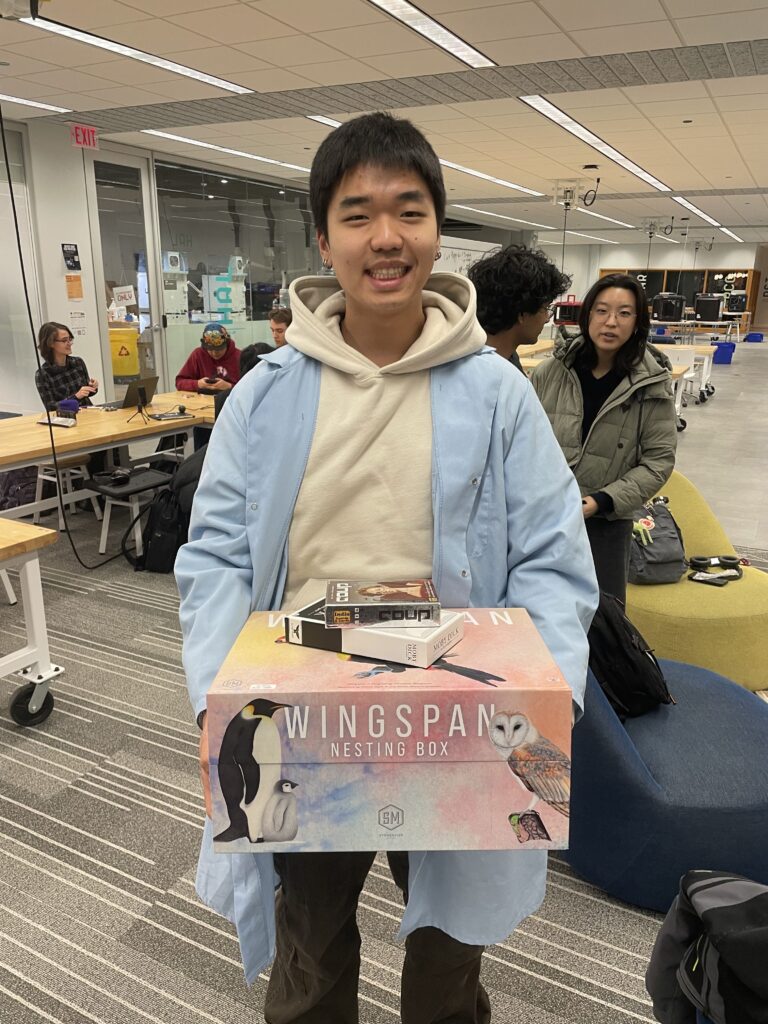

To expand our understanding of different game genres, we met up in the MADD Center one evening to play Wingspan, a game that many of us had been curious about. Our gameplay experience, while abridged for the sake of time, informed us about what an engine-building game comprises and how it plays out. We were particularly impressed with how the game’s four main mechanics (playing a bird, gathering resources, laying eggs, drawing a bird card) all kind of relied on each other– this interwoven quality of the gameplay mechanics required each player to spend their turn strategically rather than just choosing one mechanic over another for a random reason. By the end of our gaming session, while we were inspired by Wingspan and the creative potential of engine-building games, we realized that designing such a game is COMPLEX and would require a sophisticated premise that was rich in mechanic potential (in the case of Wingspan, birds and ecosystems have a whole bunch of qualities and “mechanics” to draw from). Our experience with engine-building games was limited, too, so we’d have to spend even more time playing more games and learning about the genre.

So instead, we decided to go for a social deduction game, which many of us had a lot of experience with. We started with trying to brainstorm basic premises for a social deduction scenario to be rooted in: a courtroom, with court mechanics like cross examinations and evidence? A witch trail situation, or a problem of alibis? We also thought about different sources of uncertainty. For example, most social deduction games are based on trying to find out one enemy; what if we were trying to find out who’s in one of multiple factions? What if everyone is in on the “truth,” but only one player doesn’t have the details to solve the mystery?

Given that we knew we wanted to pull away from overdone premises of one bad guy vs. an innocent group, or rivaling political operatives, we considered how else our players might be related to one another – maybe they’re working toward a common goal, and the odd man out is trying to derail the progress, or achieve some kind of opposing goal. With the idea of this malevolent character, and a second, ignorant character, in mind, we talked through a number of narrative ideas. One that we spent a lot of time with was a coding premise, where the players are writing a code, or building a computer, but one person is secretly a hacker trying to install a back door. The “back door” idea would be a potential solution to the problems of a game like Saboteur, where it can become pretty obvious who is the “bad guy” because they’re the only one obviously taking actions against the progress of the team. We considered more insidious ideas, like a back door, or some sort of unobvious pattern or path to disruption, as remedies. In the coding example, our ignorant character could be someone who lied about having a computer science degree.

We also talked about potential sources of further complexity; if we installed something closer to an engine-building component, or at least a system with inter-relating parts, the game might be a step more complex and sabotage could be more strategic and have more avenues to be hidden. This shift pushed us more in the direction of having players actively building something: a structure, an architectural feat, a bank vault, etc. We talked about the potential for red herrings, and other explanations for disruptive behavior – players could be constrained by budget, or by limited card options in their hand, and sometimes have to make less secure building decisions regardless of their affiliation. An example we kept returning to was rusty screws. Did you install them because you’re the saboteur, and you want the structure to be unsound, because they were the cheapest option, or because it was the only thing you had in your hand? This premise also makes for a decisive narrative behind a win condition: the building collapses, or the heist is successful.

A final consideration we made while brainstorming was to consider the avenues in which players are actually able to deduce who is the antagonist. We had considered ways to make the sabotage more insidious, but we considered adjusting so that as play continues and end game approaches, more of the saboteurs specific goals get revealed. This would add a memory component, and get around some of our self-imposed obstacles to deduction, but could also be difficult to balance so that the antagonist never became immediately obvious.

At the end of this first brainstorming session, we decided we had a collective idea of what kind of game we wanted to create, and lots of ideas for how to eventually make it unique and complex, but needed to play more games to get a clearer idea of how some of our mechanics and the balancing of the game could play out. We found ourselves somewhat bound by our existing experience in social deduction games (and our recent foray with Wingspan) and wanted a broader selection to work with before trying to nail down our ideas. We narrowed our conversation to the clear, agreed-upon elements that our team was excited to share in class tomorrow, and decided to regroup when we’d had a chance to play some of Ashlyn and Bruno’s recommendations.

We walked in set on a social deduction game… and walked out with a newfound love for building games. While completely different from what we had in mind, we were recommended to focus more on this building aspect of our brainstorms when pitching our idea. While it is a shame to see our social-deduction ideas go, we were excited to try out what sort of building games we could play – as such is the ordeal of a designer. Ash and Bruno recommended a couple of games to help kickstart our ideas of creating a building board game.

The first game we played was Tokyo Highway, a rather simplistic yet high-stakes game that can, at any point, put its players into shambles. There was no board, but instead a multitude of popsicle sticks/”highways” and shapes/”buildings”, and of course our cars. The goal of the game was for each player to create a highway and try to set the most amount of cars on their highways as possible. The point system was interesting in that it encouraged players to play dangerously close to other highways, creating instances of players going over or below already existing roads to earn points. However, the coolest part of the game was it’s sort of Jenga mechanic. When players build their highways, they have to make sure to not destroy or disrupt other highways otherwise they lose precious resources and in turn points. This made way for some crazy, high-tense moments where we were all holding our breaths when placing a road or a car down.

Here is us playing the game, making sure to put a highway ever so carefully…

Annnd then here is the aftermath after Ben knocked his highway down…

The chaos this mechanic brought made a game about building highways EXTREMELY fun. It was nice to play a game that didn’t require too much thinking or cards, but rather relied on the players’ careful hands.

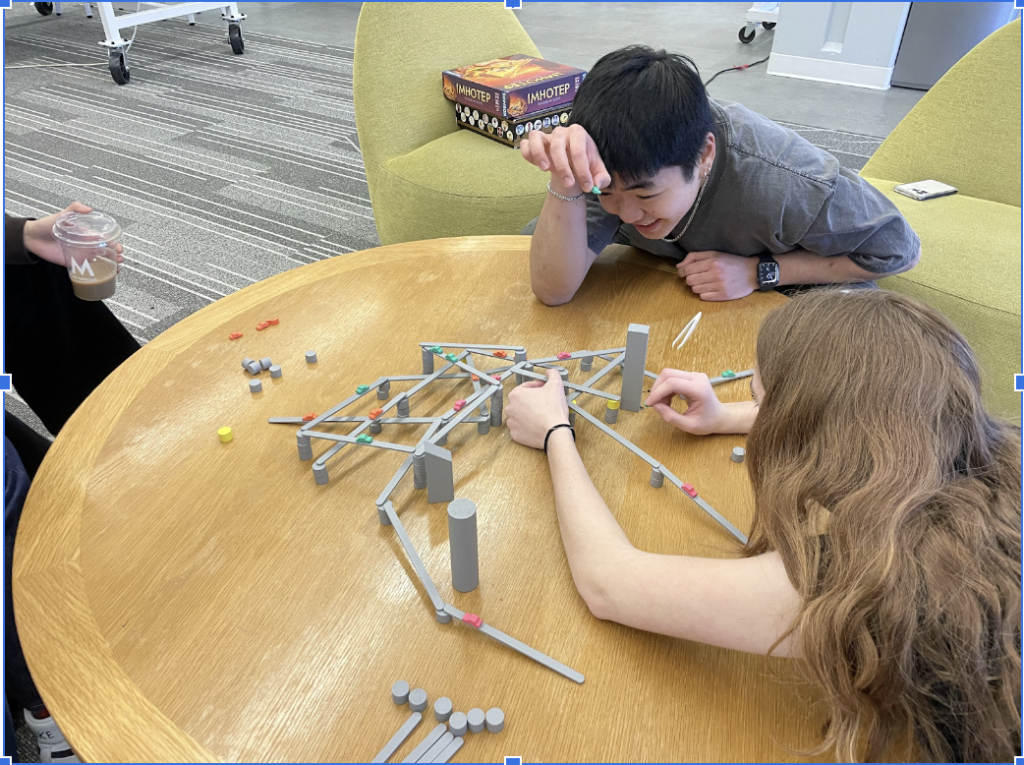

The second game we played was Imhotep: a material managing game where there is a clear motivation for players to obtain points. A bit different from the previous game, but still a very high-paced game where the players try to reach specific sites of the game board to obtain points. The game’s cards offered some nice variation to the playstyle and we also really liked how each round doesn’t drag. We were curious as to what kind of strategies we could use with the game, as it is hard to tell with such various cards – a pro to the game?

With those games played our group was set on trying to develop some building-esque board game. During our next meet up, we further developed our ideas, fleshing new areas out while also scraping others. We had ultimately scrapped the idea of a social-deduction game, alongside the mechanics of an incompetent player or a saboteur, and instead focused on creating a unique building game where the players all have clear motivations on earning points while still providing a challenge in building their structures. We really liked how Imhotep provided a lot of ways to earn points alongside Tokyo Highway’s chaotic nature with road building.

After 2 brainstorming sessions, we came up with our game prototype Social Construct. This would be a game where each player is given a sort of blueprint for building a structure and as they build that said structure, they are allowed to earn points. Each player can choose to build on whatever structure they so choose to, but must be careful in doing so as to not knock the structure over. The game also has a leveling system for the players, encouraging them to keep placing building blocks , collecting building blocks, and in turn fulfilling the point-cards of the game so as to earn points and level up, allowing them to reap better rewards in the late game. For more in-depth rules, please refer to the game manual that we developed!

When coming up with the mechanics of our game, we wanted to take the best parts of Imhotep and Tokyo Highway. We wanted to incorporate a game where the motivations for the players were clear and easy to understand while still offering potential strategies, yet still create a sense of chaos if the players were not too careful through their play session. While the game materials are not super fleshed out, we aimed to create a construction game that encourages players to come up with their own strategy that can be foiled by the unpredictable building mechanic of our game. We hope our silent playtest expresses our rules clearly while also providing the players with an enjoyable experience when playing a building board game!

02/28

The play session gave us a lot of insight into what worked and what didn’t work when playing our game. While we did emphasize that this was a playtest and that some of our materials were not representative of the final version, we found a lot of holes in our rulebook. On a side note, we also saw a lot of positive feedback from our game’s mechanics.

Starting with the positives, we got a lot of good feedback with our build mechanic and material distribution. Players also enjoyed the “leveling up” mechanic as it gave them a sense of progression and also motivated them to keep building more structures to level up and earn points. On top of that, the playtests saw some really creative building mechanics and strategies. One player attempted to go for the strategy of actually knocking down other players’ buildings to prevent them from getting points, albeit losing their own in the process.

While this was fun to watch, it did raise concern for the strategies of the game. We were concerned that players would focus on knocking down buildings rather than constructing them. The same sentiment was also shared by other players as they saw no issue with knocking buildings. To counteract this, we added some extra balancing rules. These involved having players return to the block bank the number of pieces they knocked down, up to 5, and if they have no pieces to return, they must give up a point card. This raises the stakes significantly since players can lose blocks that they have quite rapidly and as a result end up losing their point cards and their points.

Going off of this theme of rule balancing, we had to adjust a couple other rules and mechanics to encourage players to take a certain action. We changed the amount of cards that are face up (action, restriction, point cards revealed to the player) from 2 to 3. This was to prevent any 2 boring action cards from being in play, disencouraging players from taking an action card. This applies to the other card categories. Doing this allows for more variety for the players to choose from and also prevents any discouragement for the players to draw a certain card.

One of the biggest issues we had during our playtest was actually with how our manual was structured. Everyone reads and comprehends a manual differently, and we found that in our playtest we had issues where players would jump to different parts of the rule book when the rule book had mentioned a specific mechanic. For example, in the turns part of our rule book, if there was a mention of the level-up mechanic, players would frantically search for the level-up segment. While this helps the players understand the rule, it also leaves the rest of the rules to be unread and misinterpreted. To fix this, we restructured our rule book such that the order of reading makes sense with the gameplay. Having the setup, leveling up, point cards, then building structured in that order made it so the players would have a full understanding of what goals building can bring. Before, we had building at the start of the gameplay section. While this does help in explaining the gameplay mechanic, players would jump to building and negate the rules about leveling up or scoring points, which would end up causing more confusion later down the line. By restructuring our rule book in this order, we are able to clearly get across the goals that can be achieved when building and THEN address the actual build mechanic so players can understand all the rules and incentives that come with building and scoring points.

We also found our rule book to be a bit confusing with syntax. There were some words that confused our players, which led to some open interpretation of how the game was played. To solve this, our group realized that we needed a theme involved with our game. By having a theme we can sort of associate some of the syntax with concepts and ideas that the player might be familiar with. While we don’t have a theme just yet, we wanted to raise the issue so that we can be thinking about potential themes on the backburner, hopefully solving our issue of confusing syntax with our rulebook. We also made sure to standardize the language as much as possible across all cards.

Overall, our game seemed to work fine mechanically during our playtests. We still had issues with comprehending the rule book and fine-tuning some rules and mechanics, but for the most part we were happy that we were able to show off our game and let others participate in the game and have enjoyment out of it. We hope to get better materials and structure the setup of the game in a way that is presentable for the final project. By then, we hope to have designed and produced a game that anyone can play that is fun for all.

03/06

We were excited for our next playtest with the class, especially with how the manual was structured now that we reorganized a couple sections. We now put the actual building rules at the end so that it would ensure that EVERYONE would have read the rules and mechanics before jumping straight into the building. The biggest issue we saw was how people would see the building rules, place a block, and then immediately proceed to play without even reading rules for leveling up, taking action or restriction cards, etc. Regardless, this simple change made it so that players would actually be able to have a full grasp of the rules and more consciously plan out their moves within the game.

To aid with the most recent playtest, we gave players a little guide sheet similar to the one you would see in games like Coup. This guidesheet would just highlight what each level does and how to actually achieve each level. While very helpful, our players found a couple of typos that we were not too aware of… despite that, our players found the sheet helpful in understanding and planning out their blocks to place within the game. In all, adding these smaller details actually did help our players with what kind of goals they were trying to achieve with their buildings.

The joy in playtesting however lies in how others who have not written your manual or your cards interpret your rules. We learned a lot from how players perceived our rules. Some were pretty bad on our part: not making certain action cards as clear as to what they could do, how points should be added up, etc. The biggest clarity issue came from when we can actually play our point cards: if they stack, when you could use them or if they’re in play from the start, and so forth. To fix this, we made point cards the point cards much more explicit in when they should be played or not vs point cards that can be activated once a certain build requirement is met. However, we interestingly also found out that some of our point cards were great in being unclear. The players interpreted the building rules labeled out on the point cards in their own specific way that led to some CRAZY buildings. This only added to the tension to our game alongside the sort of goofiness that comes with building games. So, we wanted to express still some level of interpretation to our players with our point cards while also making clear when they should be played. Besides the point cards however, we had a lot of confusion with the level requirements: whether it was supposed to be 4 blocks across ALL plots vs 4 blocks in each plot to level up tripped players up. We aim to make these rules much more clear in our final manual.

The feedback we received from our playtests led to a big rule change in our leveling system. We found that our players would barely reach level 3 and use the restriction cards in our play tests. This was partially due to the time limit of our play tests, but the majority of it came with the frequency of block placement and availability of the players’ blocks. We also had feedback with the point system. Our players expressed how they didn’t really enjoy spending actions to get point cards, and then spending more actions to fulfill those point cards. It made gathering points slow and at some points annoying when the priority should be placing blocks.

To fix this, we first implemented a new type of card: blueprint cards! These cards would be some rule or condition that the players must fulfill in order to gain points without the need of point cards. This gives players an opportunity to obtain points while also directing them to build in a certain fashion that is NOT optimal, opening up the game to many more goofy scenarios. So, by putting in these blueprint cards does the game already start off giving players an opportunity for points as well as give direction in how the players should build in order to win.

Out of all the other mechanics however, our leveling system took the biggest hit. We reduced the possible levels from 1 to 2, made it easier to achieve level 2 for our players (so that half the game wouldn’t be stuck at level 1), and changed the actions allowed at level 1 vs level 2. We swapped the restriction and point cards, so now restriction cards can be played at level 1 and point cards can only be played at level 2. We did this for a couple of reasons. One, so that end-game play would be focused on getting any number of points possible to edge out the competition, and two, to make the beginning of the game much more exciting. By allowing restriction cards to be played, it puts even more pressure on the players with what they can build and how they can build it following the blueprint cards. We wanted to make the game much more exciting, and so doing this would accomplish that.

With these changes, we foresaw players needing much more blocks, and so also made the change to allow players to draw two cards on every draw turn. We thought about initially changing it so that player can passively obtain blocks with every turn, but we found issues with how it would essentially negate the punishment of knocking down a building and so decided to stick with allowing players more blocks to draw on a draw turn. Now, players can choose to just take 2 pieces entirely in a draw turn. We still wanted to keep the one block limit in placing down a block as this would prevent players from burning through their supply and also allowing them to more carefully plan out their next game moves.

The playtest feedback as well as our own experiences allowed us to finetune a lot of the game mechanics and add some exciting changes to aid in the overall experience. We aimed for a very careful yet chaotic and challenging building experience, and we think that with the added rules we accomplished that experience. Players can now gather points without point cards, and, if in a pinch, can rely on the point cards to put them in the lead. We’re very proud of our final game, and think that it hits all the goals that come with creating a building block game.