The Quiet Year is a map game with an incredible amount of creative freedom that sits in an interesting area of collaborative storytelling—the players never explicitly act on each other’s words in the game’s discussions, the final decision always being completely up to the player whose turn it is. There is no veto or other such function in the game to “undo” another player’s contribution to the map and story either, which creates a very interesting environment that all players have contributed equally to, rather than the ideas of one or two players dominating the game—though of course, players can follow the model of another player if they so wish.

In this way, even though there are discussions built into the game, The Quiet Year truly does feel “Quiet” in that what a player decides to change or build on the map will always go uncontested as per the game’s rules. This effect is furthered by the fact that players do not act as specific characters in their story/on their map, but rather more generalized social forces or ideas; the people in their post-apocalypse survival camp/town don’t really have voices at all.

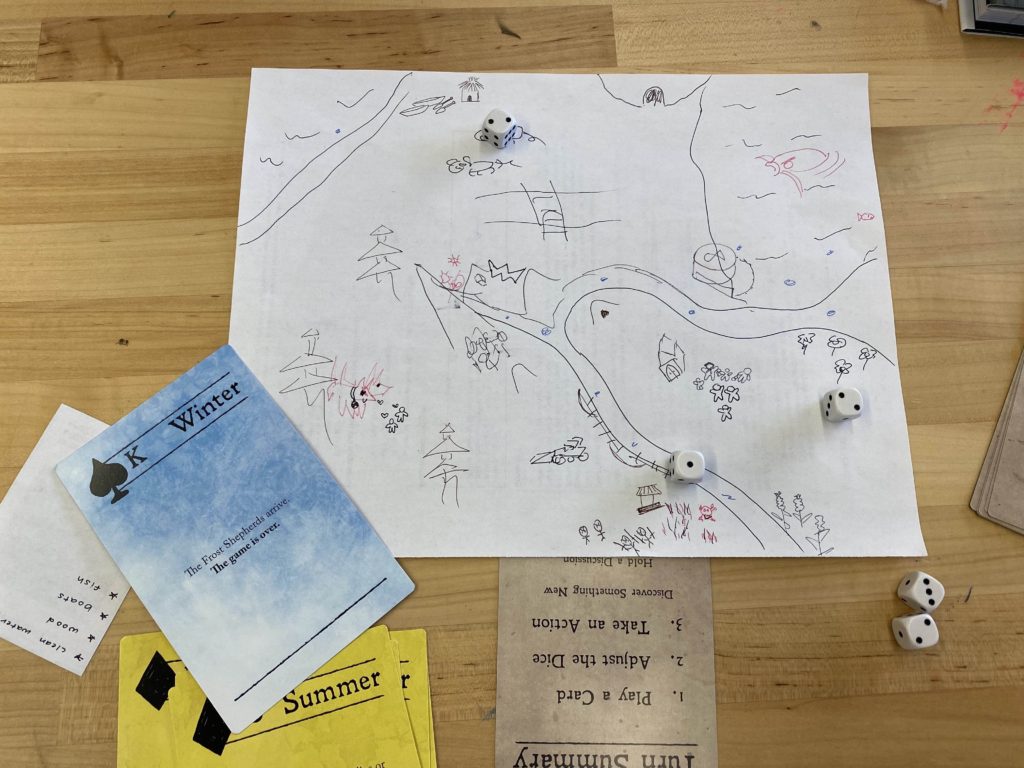

Indeed, it’s in this way that the game is truly an environmental storytelling game—on top of being literally a map game in which players draw an evolving map of the setting and everything in it. The game mechanics of how time works is on a very high scale: each turn is equal to a week, and as such events and projects feel stretched out in time, and there’s no explicit action. When outsiders arrive, they arrive and get drawn somewhere on the map, but there’s no instant conflict, confrontation, or even discussion between the survivors and the outsiders; they simply arrive, and the players discuss how people feel about it. In later turns, things may happen, but again it occurs on a large time scale; the game feels zoomed out from its events. In this way, it focuses on the environment and its slow changes, rather than the specific actions and events in real time, creating this passive, quiet observatory experience that gives the game an almost calming affect as everything unfolds.

The ending of the game, as a result, feels incredibly abrupt—nothing happens over time, there’s no indication of when it may happen, but the Frost Shepherds simply arrive and the game ends. It’s up to the players to discuss what exactly the Frost Shepherds are and how they eliminate their survivors, which continues to fit in with the game’s very open-ended nature. The jarring effect of this ending feels somewhat unsatisfying in the way it jolts players out of the reverie of gameplay.

Perhaps a better solution could be instead of having the Frost Shepherd card appear randomly in the Winter deck, it could always be placed as the last card, and as such feel somewhat less abrupt, or there could be a separate “final month” deck where multiple cards can build up to the ending, so as to transition more smoothly from the very quiet, slow experience to the sudden ending.

It is worth mentioning that, in my playthrough of the game, the Frost Shepherd card was one of the first, if not the first Winter card that was drawn, so it’s certainly possible that the game already naturally has this process in the Winter deck, and that we were unlucky enough to draw it too early.

Regardless, the game made for a very immersive and calm experience that was only ever truly interrupted at the very end; the mechanics of its timescale, turn taking, and roleplaying method all contributing to that affect.